Life Science Development’s Guarded Prognosis

Is there a cure for the post-pandemic lull?

As of early spring, thousands of jobs had been eliminated at several major health agencies. How much these cuts will affect drug development, and ultimately the demand for space, remains to be seen.

Perhaps more consequential in the short term, the quantity of space delivered in the major life sciences markets across the country from 2019 to 2021 substantially outpaced demand, reported Joseph Fetterman, an executive vice president at Colliers. “Without a dramatic increase in funding for promising drug development activity, it could take three to six years to absorb the existing surplus in many markets,” he said.

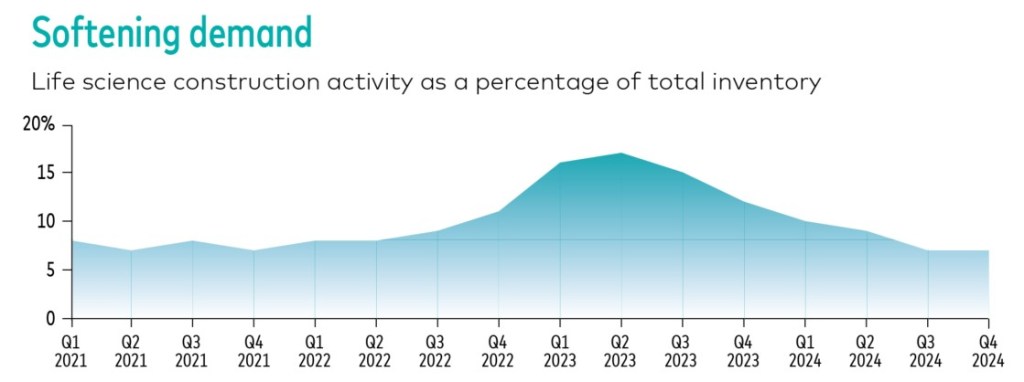

Signs of softening characterize the life science market’s fundamentals. Net absorption was negative again in 2024, as the nationwide vacancy rate ticked up 250 basis points to 20.5 percent from the second quarter to the end of the year, according to Cushman & Wakefield’s recent life science update.

Development is slowing, as well. Although 16 million square feet were under construction at the end of 2024, only 2 million square feet are in the pipeline. Rent growth was mixed, as Chicago, Denver and the Los Angeles-Orange County region gained, while the growth rate slowed by double digits in Boston and New York City.

The nationwide vacancy for lab space is about 26 percent, reporter Kevin Wayer, president of JLL’s global life sciences division. While aiming to stay cautiously optimistic, he observed that “there’s a fair amount of space to work through.” Last year the top 25 life science-focused venture capital firms raised about $15 billion, added Wayer.

Venture capital: Still a fan

One encouraging trend that may point to long-term demand for new life science product is continued strong interest from venture capital. Reversing a two-year slide, last year life sciences firms raised $26 billion, up from $23.3 billion in 2023, according to JP Morgan’s annual report. As BioMed Realty CEO Timothy Schoen noted, that surpassed both pre-COVID and long-term averages.

Fundraising increased year-over-year in each quarter, and 98 companies raised rounds of $100 million, beating the total for each of the previous two years. This year, venture capital activity (will be) focused on mega-rounds—$100 million-plus investments in companies with proven product data, predicted Ryan Shannon, executive vice president of finance at IQHQ.

Biotech and pharmaceutical companies are also funding growth through a variety of other approaches, including IPO activity, M&A, private investment in public equity deals, and VC raises at later-stage private companies. “These companies are accelerating their growth objectives in order to backfill revenues from near-term patent expirations while also seeking new value-creating investments,” said IQHQ Co-CEO Tracy Murphy.

Beyond the big three: emerging hubs

Though life science real estate continues to be dominated by the big three—the San Francisco Bay region, San Diego and the Boston–Cambridge hub—there is no shortage of activity in other markets. An attractive location and a vibrant university presence help create the conditions for a plethora of mini-hubs across the country. According to an analysis by Pitchbook, six markets attracted at least $75 million in public and private life science investment last year: Austin, Indianapolis, Houston, Phoenix, Dallas–Fort Worth and Salt Lake City.

The locations named by life science real estate experts indicate the remarkable diversity of these niche markets. Timothy Schoen, CEO of BioMed Realty, cites Boulder, Colo., home of a University of Colorado campus. Pittsburgh, Minneapolis, Salt Lake City, St. Louis and New Haven, Conn., all get a thumbs-up from Joseph Fetterman, an executive vice president at Colliers. For Jeffrey Myers, a Boston-based research director for Colliers, at least three Sun Belt markets make the grade: Houston, Nashville and Birmingham, Ala.

New mini-hubs are springing up next door to the big three, as well. Somerville, Mass., a Cambridge neighbor, had no purpose-built lab space before the pandemic, but today boasts more than 2 million square feet.

“When the market was white-hot, developers were able to spread out from traditional nodes, and tenants were forced to follow,” Fetterman said. “Somerville benefitted from this trend and its proximity to well-established clusters in Cambridge.” A high-profile example is 10 Prospect St., completed in 2023 by a joint venture of Magellan Development Group, RAS Development, Cypress Equity Investments and Affinius Capital. The 205,000-square-foot building is a part of the venture’s $2 billion, 1.5 million-square-foot USQ project.

In Philadelphia, the Station District is emerging around Amtrak’s 30th Street Station as a mini-hub in the University City submarket. As Fetterman notes, the neighborhood has been gaining momentum since Brandywine converted the former Bulletin Building to a 50,000-square-foot R&D headquarters for Roche’s Spark Therapeutics.

At Cira Centre, the 29-story trophy tower adjacent to 30th Street Station, Brandywine converted multiple floors to lab space and launched an incubator. All told, the Station District now has 1.15 million square feet of purpose-built development scheduled to deliver in the first half of this year, including a new 500,000-square-foot Spark/Roche manufacturing facility, and 50,000 square feet of space conversion in the works, as well as a proposed 185,000-square-foot purpose-built lab project.

Quest for construction capital

Construction financing paints a tighter picture. The bar for securing life science financing is very high in today’s environment, noted Wayer, “but for the right projects, capital is still available.” Those projects are typically characterized by diversified rent rolls or investment-grade tenants.

He noted that the biggest players of pharma, biotech and medtech have less need for outside capital, as they can use cash proceeds from operations and M&A for manufacturing, lab or office space. Otherwise, construction financing can be extremely challenging, though public capital participation can help solve some of the gap financing needs. “You’ll start to see some creativity around that,” he predicted.

Another key factor in new development at a time of surplus space—landing an anchor tenant. That’s what led to a major project in Kendall Square, the life science cluster near the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass. In March, Biogen signed a 15-year lease with a joint venture of MIT Investment Management Co. and BioMed Realty for a 580,000-square-foot headquarters building at 75 Broadway, which is scheduled to open in 2028. That project will follow the debut of another major Kendall Square development: BioMed’s 585 Kendall, a 637,000-square-foot building anchored by Takeda Pharmaceuticals and scheduled for a 2026 opening.

“Given the record-high vacancy rate in the submarket, without a tenant in hand, the developer of this project would not likely have been able to move forward,” said Jeffrey Myers, a research director with Colliers. “Very few lab buildings are breaking ground these days, and those that do typically involve projects with anchor tenants and strong sponsors.”

The most active lenders for life science development include national and major regional banks, debt funds (such as Square Mile Capital and Blackstone Real Estate Debt Strategies) and life science-focused investors such as Alexandria and King Street, which provide debt as well as equity.

“With a preference for Tier 1 life sciences clusters, construction debt is 150-250 basis points higher than a year ago,” said Fetterman. “In addition, leverage has compressed with loan-to-cost levels at 60 percent or below.” Rising construction costs are pushing lenders to underwrite construction deals with 10 to 15 percent contingency, he added.

Why bigger is better

When it comes to project size, large life sciences campuses can provide significant advantages, according to executives. Locations offering plenty of room for collaboration, retail options, amenities and access to transportation will continue to dominate the sector, said Murphy’s IQHQ. She cites the firm’s 2024 delivery of three projects comprising 1.9 million square feet of new construction and the expected debut this year of 1.4 million square feet in the core markets of San Diego, the San Francisco Bay region and Boston.

In February, IQHQ secured a landmark lease at Elco Yards, its 670,000-square-foot mixed-use development in Redwood City, Calif. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative committed to 225,000 square feet for biomedical research and AI-driven science initiatives and will occupy its new space in 2027, Murphy said.

Although big campuses have historically been the domain of big pharma, over time this tranche has been shedding older R&D and manufacturing sites. “Developers have acquired these campuses as suburban life science campuses, leasing portions of the park and redeveloping less marketable, underdeveloped or undeveloped parts of the campus,” added Fetterman.

He expects almost all new development in the near future to be individual build-to-suit buildings or projects, led by an anchor tenant with a specific need that can’t be satisfied by existing inventory. “With the inventory of purpose-built R&D buildings, it is likely that in the near term we will see more redevelopment or new development for specialized (Current Good Manufacturing Practice) requirements.”

Life sciences campuses are a key solution not only for larger firms but also for smaller firms, which can benefit from participating in an ecosystem of companies, people and ideas, executives say. “Unlike other industries where companies can operate remotely, life sciences rely heavily on in-person collaboration—lab work simply can’t happen over Zoom,” commented Sonia Taneja, west region market leader & managing director at King Street Properties. “This commitment to physical spaces has kept demand in established life science clusters.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.