December Issue: Don’t Miss these Investment Warning Signs

Are risks and returns getting out of balance?

By Hugh F. Kelly, PhD, CRE

Real estate is a residual product of the economy. It gains value when and where the economy is robust, as well as when and where the property contributes to productivity. When the opposite conditions prevail, they impair asset value. Boom towns—such as those that sprung up recently in the North Dakota energy fields—created residential rents that, for a time, rivaled those of the most expensive coastal cities. Yet that boom has fizzled, along with prices at the pump, and real estate values have quickly dropped back to earth.

Real estate is a residual product of the economy. It gains value when and where the economy is robust, as well as when and where the property contributes to productivity. When the opposite conditions prevail, they impair asset value. Boom towns—such as those that sprung up recently in the North Dakota energy fields—created residential rents that, for a time, rivaled those of the most expensive coastal cities. Yet that boom has fizzled, along with prices at the pump, and real estate values have quickly dropped back to earth.

The limit case, of course, is the ghost town where the gold or silver mine has shut down, the population has left, and all the buildings have been abandoned. Nor is the West the only part of the country where you see this phenomenon. A tramp through the woods in upstate New York, rural Massachusetts or Connecticut sometimes reveals old forges, stone walls, and chimneys—traces of long-ago habitation in places reclaimed by nature.

I don’t mean to be an alarmist, but it is sobering to remember that risk lurks in every real estate investment, and that risk is not evenly distributed across the American landscape.

My thoughts were prompted by the latest data on investment. As this is written, we have data from Real Capital Analytics (RCA) showing $375 billion in commercial property investment encompassing 23,341 deals during the first three quarters of 2015. The concentration—and the dispersion—of that investment activity are worth a thoughtful look.

Some of the data seems to make perfect sense. For instance, in the office sector RCA tallied $108 billion of investment through September, 45 percent of it directed to primary cities. Secondary markets came out slightly ahead, accounting for 45.9 percent of total purchases (by price). But this is understandable, since major markets such as Seattle, Denver, San Jose, Dallas and Atlanta are typically classified as secondary. Although there are no performance guarantees, these are all metro areas with mature, diversified economies and significant stocks of high-quality buildings. Such markets are worth attention, especially from alpha-oriented investors who believe that astute timing and careful asset selection can provide superior yields at a time when primary markets are very richly priced.

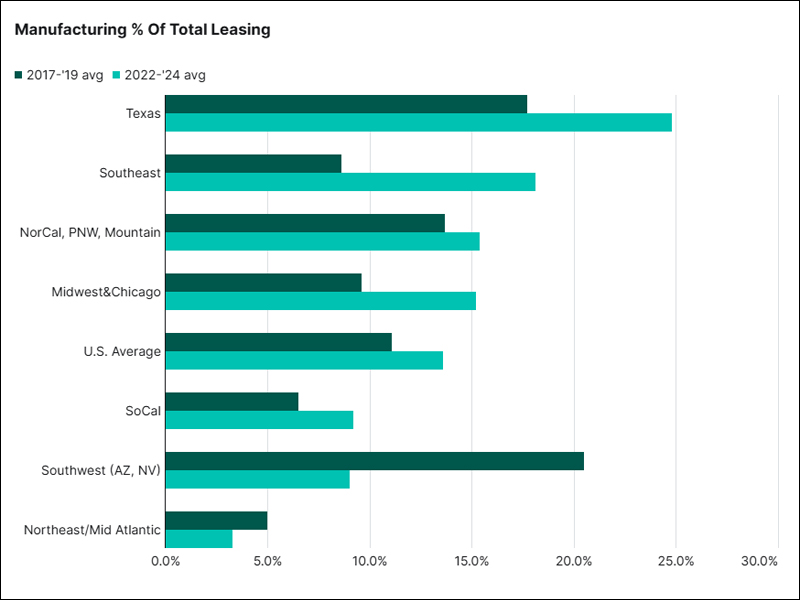

In the industrial sector, which attracted about half as much investment capital as the office sector—$50.7 billion—the geographic distribution of activity was different, yet still plausible. Primary markets like New York City, San Francisco and Washington, D.C., have largely post-industrial economic bases. It is not surprising to see primary metros capture just 18 percent of industrial property investment, while 65.5 percent is going to the secondary markets. The 16.5 percent share captured by tertiary markets, especially in the Southeast, reflects where the nation’s light manufacturing and warehousing operations have moved to take advantage of better operating costs and logistical efficiency.

Wanted: Tough Questions

However, I believe that some other trends should give us pause. For example, what are we to make of the choices of hotel investors? Hospitality purchases during the first nine months of 2015 totaled $35.6 billion, with 61.7 percent going to secondary markets and an incredible 23.9 percent to tertiary markets. Since hotel demand stems from three major sources—business travel, domestic tourism, and international visitors—how can nearly a quarter of hotel acquisition capital flow to tertiary markets, where demand from all of those crucial sources must be regarded as thin?

Retail acquisition patterns, too, raise serious questions. In an era where final demand is still lagging, and the shopping center market remains burdened with residual oversupply, how is it that tertiary markets commanded 26.9 percent of the $65.2 billion invested in the sector, while primary markets managed only a 15.9 percent share? Are we expecting a sudden reversal of urbanization trends? Are the sprawling, low-density towns and cities of America likely to be retail overachievers in an era where e-commerce is already capturing more than 7 percent of consumer purchases? What will generate the returns on retail property investment in tertiary markets over the next five to 10 years?

Finally, it is time to question whether the apartment investment boom is getting ahead of itself. In 2014, there was more capital directed to the multifamily sector than at the peak of the housing boom a decade ago. By September, the $98.3 billion of rental apartment acquisitions had already matched the total for 2014—and transactions usually surge during the final quarter.

If there is a risk that “Niagara of Capital” conditions will return, when too much money surges into a property sector, that risk is most evident in multifamily. And 67.4 percent of that capital is going to the secondary markets: Dallas ($5.4 billion), Atlanta ($4.7 billion) and Phoenix ($2.4 billion). All three have long histories of overbuilding and intense competition for rental growth.

Right now, the real estate markets are feeling very good. The consensus seems to be that we have a couple of years ahead before the threat of the next down-cycle. But it is during eras of good feeling that discipline and selectivity tend to relax. The data on capital flows should at least tell us that there are risks in spreading our nets too wide in search of lower prices and higher yields in the commercial property markets. Most often, you get what you pay for.

—Hugh F. Kelly, PhD, CRE, is a clinical professor of real estate with the NYU Schack Institute of Real Estate and was the 2014 chair of the Counselors of Real Estate.

You must be logged in to post a comment.