Office Debt: The Underwater Mountain

A wall of troublesome maturities is coming due in the next five years. What’s next?

To get a glimpse of the office market’s plight, you need only take a short stroll down Jackson Boulevard in downtown Chicago. Defaults totaling $404.5 million triggered foreclosures on four buildings within a few blocks during the past year, including a 1.4 million-square-foot tower owned by Brookfield Properties.

Similar scenarios are playing out across other major U.S. office markets, and defaulting landlords often walk away, leaving the keys on the table. Lenders typically list the buildings for sale or try to auction them, but that’s hitting some headwinds. In a research paper published last year and revised in December, economists with the National Bureau of Economic Research stated that the collateral underlying 44 percent of all office loans appears valued below the loan balances. In a word, they’re underwater.

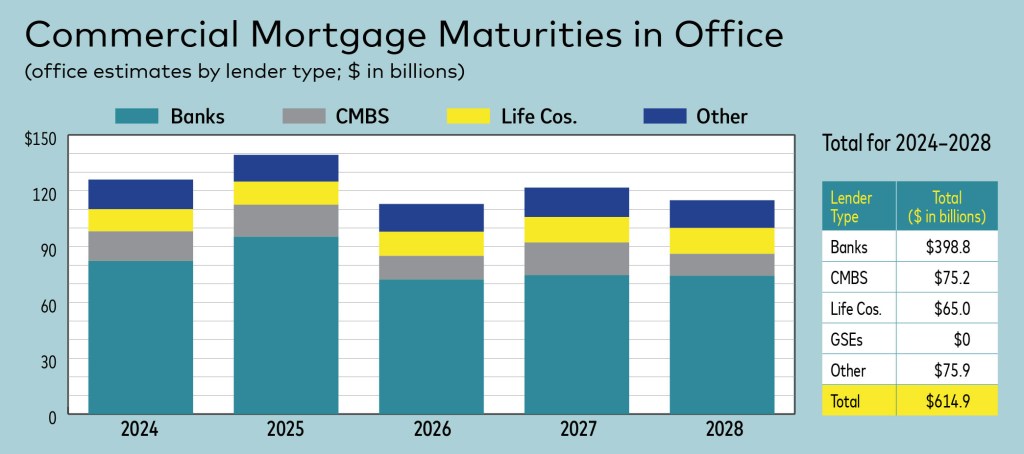

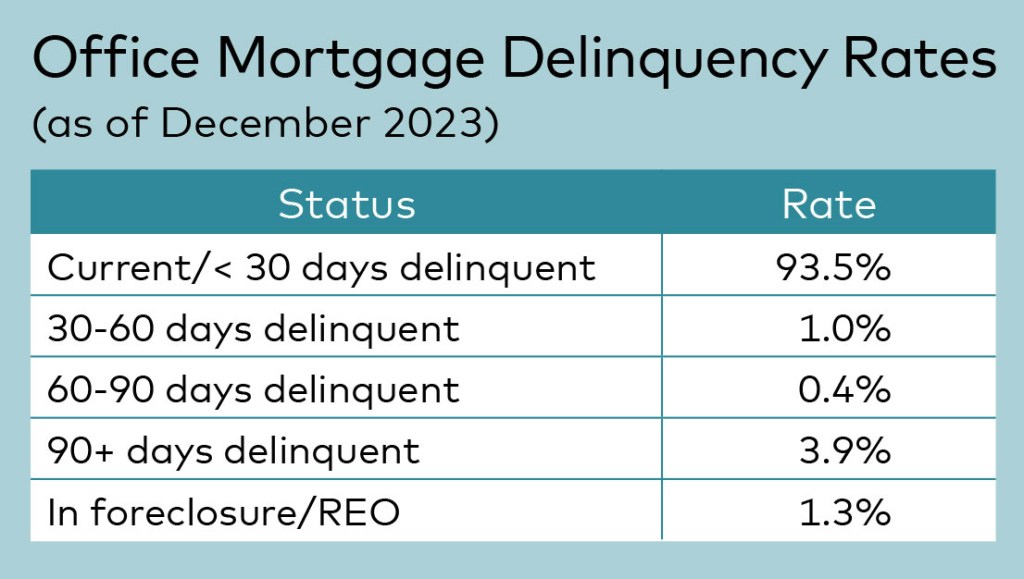

Ultimately, disruption from the pandemic and rising interest rates could deliver tens of millions of square feet of unwanted office space into the hands of lenders. According to Trepp, some $615 billion in office loans will mature over the next five years. Some of that amount could be pushed out through loan extensions. What’s more, the office delinquency rate jumped to 6.5 percent in the fourth quarter last year, a 140-basis-point increase from the third quarter, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

The most charitable view

“It’s challenging—that would be the most charitable view of the office market,” observed Ben Kadish, president of intermediary Maverick Commercial Mortgage. “Eighty percent of lenders have redlined office loans because they already have too many on their books and they don’t know what to do with them.”

Considering that only a thin slice of offices can be converted, many lenders are hoping they can kick the can down the road and cut their losses once interest rates tick down and workers return with more regularity. That might be too optimistic relative to where the market is today, said Lonnie Hendry, chief product officer at Trepp. Absent a deep recession or unexpected disruption in the economy, a government bailout like the Troubled Asset Relief Program, commonly known as TARP, some 15 years ago is hardly likely either, he added.

“You can’t underwrite a pandemic. And you can’t underwrite a 400-basis-point spike in interest rates.”

—Debra Henderson Morgan, Managing Director, CohnReznick

“The best and highest use for most of these sites is still going to be an office building—but a super modern, highly amenitized office building,” Hendry added. “Imagine going to investors and saying, ‘Trust us, we’re going to tear down this office building that nobody wants to occupy, put up a brand new one, and then people are going to come back.’ That’s a pretty hard sell.”

Financial crisis redux

New and modern Class A properties have fared well in the current environment, Kadish observed. Older Class B and C properties that are either functionally obsolete or on the border account for the lion’s share of office property distress.

More specifically, U.S. offices built after 2010 recorded 1.7 million square feet of positive absorption in the fourth quarter of 2023, according to CBRE. That reflected a relatively consistent trend since the start of the pandemic, the brokerage firm reported, and the average vacancy rate of 15.2 percent was 340 basis points below the overall national vacancy figure of 18.6 percent.

Analysts also downplay the threat the office maturity defaults pose to banks. In an early March vlog on commercial real estate mortgage foreclosures and extensions, Marcus & Millichap chief researcher John Chang acknowledged that the office sector faced unique work-from-home issues. But he likened the risk the defaults posed to the banking system to a “ripple” vs. a “tsunami.” Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell echoed those sentiments in front of Congress a few days later.

Still, discussions of bank risk as it relates to office loan defaults and other real estate debt weren’t supposed to happen. Following the Great Financial Crisis, regulators and financial institutions strengthened underwriting to prevent overleveraged deals. Remember Harry Macklowe’s $6.8 billion purchase of seven Manhattan skyscrapers in 2007? He used $7 billion in loans and only $50 million in equity to finance it.

As banks and the CMBS market regained their footing a decade ago, they generally required 30 to 35 percent equity in deals, said Debra Henderson Morgan, managing director in the restructuring and dispute resolution practice of CohnReznick. But now borrowers and lenders find themselves back where they were during the GFC—in both eras, office devaluations wiped out equity. In a best-case scenario today, a distressed property’s value is equal to the outstanding loan amount, added Morgan, who represents sponsors and lenders in workouts.

“I’m working with a lot of Class B and C properties that are valued at 50 percent of the debt, and the buildings could be anywhere, in downtowns or the suburbs,” she remarked. “You can’t underwrite a pandemic. And you can’t underwrite a 400-basis-point spike in interest rates.”

How did the market get here? In short, a double whammy:

1. The pandemic-driven lockdowns showed that remote work could be productive to a good degree—although the jury’s not completely out on that. This, however, ushered in a radical change in behavior—organizations realized they could operate in much less space, and employees got a taste of a more flexible and commute-free arrangement.

As a result, the national vacancy rate hit an all-time high of 19.7 percent at the end of 2023, a year-over-year increase of 200 basis points, according to Cushman & Wakefield. CBRE reported that roughly 180 million square feet of sublease space was available at the end of 2023, a 30-basis-point decline from the peak earlier in the year.

2. The Federal Reserve’s abrupt end to a years-long zero-interest-rate policy fractured the property markets by propelling the cost of capital upward of 400 basis points. Combined with the hybrid work trend, it fueled maturity defaults and drove office values across the U.S. down an average of 35 percent since their early 2020 peak, according to Green Street’s March price index report.

Analysts like Goldman Sachs say a dearth of office investment sales and liquidity are hindering true price discovery, which suggests an even greater value loss is probable. Earlier this year, for example, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board sold its 29 percent stake in Manhattan’s 360 Park Ave. for $1 to its partner, Boston Properties, which also assumed the investment group’s share of the debt.

“I don’t think there has been a new invention in office space since the 1700s.”

—David Frosh, CEO, Fidelity Bancorp Funding

What to do?

As much as the acceleration in interest rates fueled a bid-ask stalemate among buyers and sellers of commercial properties beginning some 24 months ago, so too has it created a standoff between office lenders and landlords. While buyers and sellers can elect not to pursue a deal and come to no harm, lenders and building owners lack such a clear path. Here are some of their options:

Extend and pretend. Foreclosures are ticking up, but lenders and sponsors have primarily focused on office loan extensions and modifications, especially as each year brings new maturities. Regulators are encouraging the agreements. In June 2023, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the Federal Reserve and other agencies encouraged banks to work with creditworthy borrowers in distressed times, reiterating and updating guidance introduced in 2009.

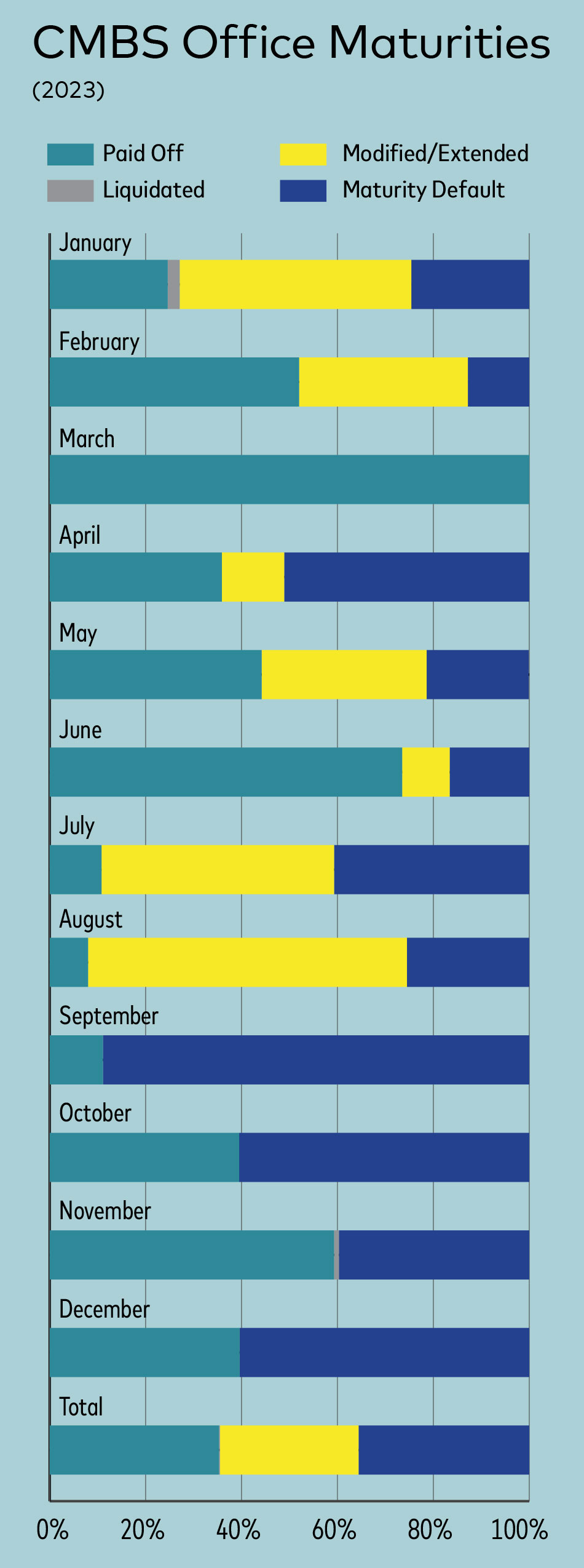

In his vlog, Chang estimated that $89 billion of distressed office debt maturing in 2023 had been pushed into 2024—unsurprisingly, more than any other property category. But in most cases, the borrower has to bring some cash to the table, typically to pay down the loan or fund tenant improvement, cash flow or other reserves.

Early this year, Paramount Group and Blackstone agreed to pay down $125 million of an existing $975 million office CMBS loan on the 1.6 million-square-foot One Market Plaza in San Francisco. In return, the landlords received a three-year extension with an additional one-year option, and agreed to a 5-basis-point interest rate bump to 4.08 percent. While the building is 96 percent occupied, it faces significant lease expirations in the next few years.

“There’s going to have to be some contraction in the office sector—probably 20 to 40 percent of these non-viable assets—for the market to get close to equilibrium.”

—Lonnie Hendry, Chief Product Officer, Trepp

The question, Hendry says, is whether borrowers who inject capital to extend an office loan in default on lesser buildings will be willing to plow another slug of capital for a further extension if the current market doldrums persist.

“That’s where the rub will be,” he said. “If a borrower wants to extend but doesn’t want to put in fresh capital, will the lender threaten to take back the property or agree to another extension and hope that the macro environment changes?”

Refinancing. The refinancing option has been decidedly less popular—lenders typically want to avoid refinancing someone else’s bad loan. Focusing solely on office CMBS, 80 percent of the $15.2 billion in loans maturing in 2024 have performance characteristics that will make them difficult to refinance, according to Moody’s. That doesn’t include the $5.6 billion in 2023 CMBS office maturities that were extended or in maturity default.

Still, refinancings are not impossible, observers say. Location, submarket, building age, occupancy, the cost basis and rent roll are elements lenders scrutinize. But as with extend and pretend, lenders typically want a substantial equity infusion to bring down leverage to more appropriate levels. The unwillingness of sponsors to do that, along with the lack of conventional financing for offices, narrows the field to opportunistic lenders, who are charging upward of 10 percent for bridge financing, said Jeffrey Erxleben, president of debt and equity for Northmarq.

“If a building is outside the box—with the box being well-leased and occupied, with current cash flow—borrowers are going to have to find more expensive opportunistic lenders,” he said. “But in theory, it’s going to give them time to execute a business plan and refinance it on better terms in a short amount of time.”

The size of the deal matters, as well. Lenders are more willing to dole out small amounts of debt (for well-performing buildings). In February, for example, Maverick arranged a five-year, $2.4 million loan to refinance a 30,000-square-foot office building in downtown Indianapolis.

Foreclosure. Foreclosures have historically been considered a last resort, yet they are becoming more common as efforts to extend or modify loans sputter. Increasingly, sponsors are surrendering properties through deeds in lieu of foreclosure.

Today, voluntarily giving up buildings makes sense, considering that, as a result of financial crisis reforms, loans may convert to recourse for sponsors who fight foreclosure, Morgan observed. Lenders may also place the property into receivership, which could present tax problems for sponsors.

“It’s challenging—that would be the most charitable view of the office market.”

—Ben Kadish, President, Maverick Commercial Mortgage

“One of my concerns about this market is what I call ‘perpetual receivership,’ where a lender assigns a receiver and three years later the receiver is still making monthly reports,” she said. “The building stays in the name of the owner and their tax ID, but someone else is managing the investment.”

Buildings sold in foreclosure auctions reveal remarkable value losses. In February, the Montgomery Park office building in suburban Portland, Ore., returned to the lender for a credit bid of a mere $37 million after the borrower defaulted on some $150 million in debt. The property had sold for $255 million in 2019.

Following Retail

In a roundtable discussion of the economic outlook for 2024 hosted by Marcus & Millichap in January, a panelist specializing in shopping center investment recalled telling her office investment colleagues that office was undergoing a “secular reckoning” similar to what retail went through years before. The transition to a work-from-home mentality and the spike in interest rates are to office what category killers and e-commerce were to retail.

One difference, however, is that after people were cooped up in their homes fulfilling all their needs via Amazon during the lockdown, they were eager for action as the crisis eased and went out to eat, shop and vacation. Remote workers haven’t shown the same enthusiasm for a full-time return to the office, and companies are still deciding how much space they actually need.

Reporting from Kastle Systems and Placer.ai, two firms that have been tracking the return to office, indicates that office occupancy hovered between 50 and 70 percent of pre-pandemic levels in any given week or month over the past year.

Another difference is that retail managed to reinvent itself through smaller footprints, better inventory control, new entertainment concepts and omnichannel sales strategies, to name a few strategies. At the same time, the retail sector culled unwanted space from the market: U.S. square feet per capita dropped by about 3 percent from 2008 through 2022, according to CBRE.

You must be logged in to post a comment.