Tariff Uncertainty Revs Up Demand for Manufacturing Space

New levies on foreign countries are only the latest spur to the return of manufacturing space.

Immediately after signing the One Big Beautiful Bill Act in early July, President Donald Trump turned his attention back to tariffs. The move seemed to generate less tumult in the equity markets as previous announcements did in April. But, in any case, it raised the prospect of tariff-related impacts broadly for the economy and more narrowly for CRE.

For the industrial sector, the prospect of tariffs, while seemingly urgent, is only the latest stimulus for the resurgence of manufacturing space, which had been happening since even before the pandemic.

Manufacturing already has momentum, and astute developers in prime markets can take advantage of it—provided they have the specialized skills necessary.

“The drive to develop manufacturing space in the U.S. in the last five years has been strong,” said Erik Foster, principal & co-lead of industrial capital markets at Avison Young. “Tariff-related challenges have only heightened the urgency for domestic production capabilities, suggesting that demand for U.S.-based manufacturing space could increase even further in the near future.”

Impacts of uncertainty

On-again, off-again tariffs have created a considerable amount of uncertainty in the U.S. economy. But CBRE Americas Industrial & Logistics President John Morris points out that U.S. manufacturing growth and development is less immediately impacted by economic forces than distribution. Distribution space is strongly associated with retail, which is driven by consumer spending.

“These manufacturing decisions are 20- to 40-year decisions, so they’re less responsive to economic changes,” Morris observed. “The same goes for policy changes. We’re talking about a policy umbrella in a four-year window, and we’re trying to figure out its impact on 40-year decisions.”

On the other hand, the industry is aware of the potential policy changes that might spur demand for manufacturing space in the United States. Such awareness would take time to translate into further development, but it could happen.

“The amount of leasing that’s attributable to manufacturing is only marginally bigger than it was a year ago, so right now, the leasing numbers don’t say that tariffs are driving property use by manufacturing,” Morris said.

But there is a significant increase in conversation around possible requirements.”

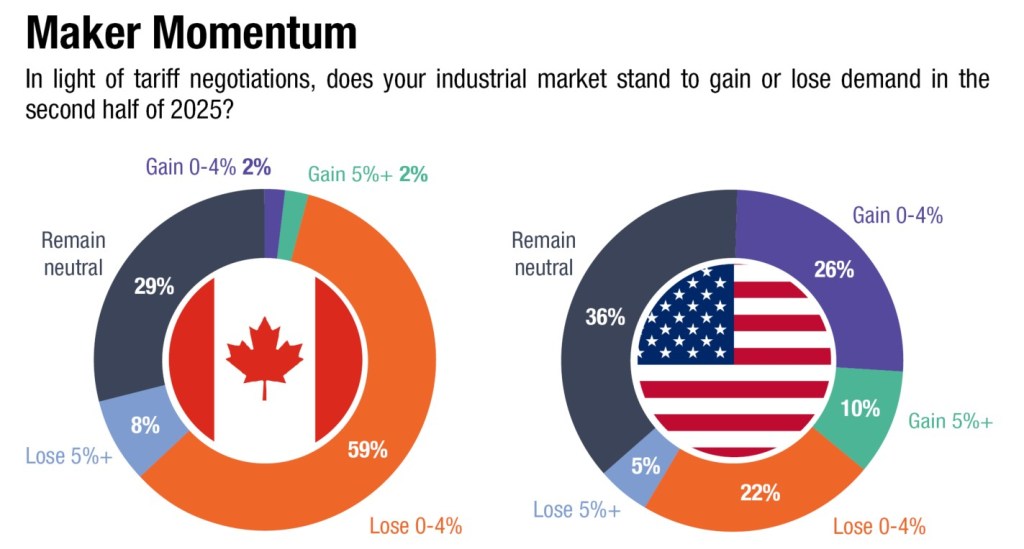

According to the results of an Avison Young survey, U.S.-based industrial real estate specialists are divided on the impact of tariffs on their markets, with the largest share saying it will have a neutral impact (36 percent). A smaller percentage (26 percent of respondents) believe there will be a net gain in demand of 4 percent at most), while 22 percent say there will be a net loss of that size.

North of the border, the prospect of tariffs is having a somewhat different impact, according to Avison Young Principal Marie-France Benoit, director of market intelligence, Canada.

Every place has an interest in drawing jobs, but it’s also very much a matter of whether or not they’re investing in business attraction.

—John Morris, President, Americas Industrial & Logistics, CBRE

“The looming threat of tariffs on Canadian exports to the U.S. has introduced a new layer of short-term uncertainty, causing many companies to pause or delay plans for expanding industrial facilities,” Benoit pointed out. “With rising cost concerns and supply-chain risks, businesses are becoming more strategic—prioritizing access to talent, modern facilities and geographic reach.”

The Canadians who responded to the AY survey were decidedly more pessimistic about the impact of tariffs, which stand to slow trade all together. More than half (59 percent) predict a loss in demand for industrial space of at least 4 percent, while only 29 percent say the impact will be neutral.

Efforts to diversify trade beyond the U.S. could reshape demand for industrial space, while growing consumer interest in locally made goods adds further momentum, Benoit says. In the longer term, federal investments in energy, infrastructure and defense are expected to drive new types of industrial development.

“These shifts could open new export markets for Canadian goods, influencing both the location and type of industrial space in demand,” she noted. In the meantime, many firms are stockpiling goods ahead of the latest tariff pause deadline.

Manufacturing returns

In its industrial tenant demand study, JLL found that demand for manufacturing space represented over 18.8 percent of the total industrial demand. This marks a more than 350 percent increase since 2018 and a 50 percent annual gain since the pandemic started in 2020. Growth is concentrated in major markets, with access to land, power, labor and advanced manufacturing needs as prime considerations.

To some extent, U.S. corporations are seeking to reverse the tide of offshore manufacturing that accelerated in the 1970s and ’80s. For a time, that strategy represented cost-cutting measures in a world with increasingly short-term outlooks (quarterly, say).

The shift left manufacturers open to new risks, which became less hidden when the global pandemic snarled far-flung supply chains. But even before that, U.S.-Chinese political tensions raised questions about too much dependence on China as a source of critical manufactured goods.

Supply chain issues and new policies are factors in the surge, but so is the fact that the U.S. manufacturing infrastructure is aging, with over 52 percent of inventory being 30 to 60 years old, according to JLL. There’s a growing demand for updated facilities that can support advanced manufacturing processes and meet modern sustainability standards.

Meanwhile, U.S. manufacturers’ shipments—a metric at the heart of the demand for facilities—are up compared to a year ago, according to the Census Bureau. In April, the total was $1.92 trillion, down 0.1 percent from the previous month, but up 3.8 percent year-over-year. Manufacturers’ inventories for April were an estimated $2.65 trillion, virtually unchanged from March 2025, but up 2.2 percent from April 2024.

A clear example of the trend toward new manufacturing facilities is the rapid expansion of semiconductor manufacturing, with major projects underway in Texas, Arizona, Ohio and other places, Foster pointed out.

Texas Instruments recently announced plans to invest $60 billion in seven semiconductor manufacturing plants across three sites in Texas and Utah, which represents the largest investment of its kind in U.S. history.

Other companies are making relatively smaller investments in manufacturing, though still sizable, such as Amgen’s $900 million expansion of its New Albany, Ohio, manufacturing facility, bringing the biotech company’s total investment in central Ohio to more than $1.4 billion.

In metro Phoenix, manufacturing accounts for 22.1 million square feet (16 percent) of starts during the 2020s so far. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. recently announced plans to invest an additional $100 billion in its chipmaking complex that began producing earlier this year.

“These massive investments are not only boosting local economies but also driving significant growth in ancillary industrial assets, such as warehousing, logistics hubs and supplier facilities, further reinforcing the momentum behind North American manufacturing development,” said Foster.

The growth in manufacturing parallels the larger expansion of industrial in the early 2020s, which partly got a boost from the pandemic.

“Declining interest rates and solid market fundamentals continue to support strong capital inflows into the sector, underscoring long-term confidence in its performance,” noted Benoit.

Manufacturing and the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

In the final version of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, commercial real estate received its share of advantages, such as the extension of Opportunity Zones.

The bill also included incentives to encourage U.S. manufacturing and manufacturing development, including a temporary tax break designed to spur investment in American manufacturing and energy infrastructure, namely Section 70307. That provision would allow businesses to immediately deduct 100 percent of the cost of new “qualified production property” put in service over the next three years.

Qualified production property means a range of assets. For real estate, that includes buildings and facilities used for manufacturing. The properties must be new, within the United States and put in service between 2025 and the end of 2028.

The law also makes it cheaper for semiconductor manufacturers to build U.S. plants, a measure that builds on the Biden administration’s efforts to strengthen its domestic chip supply chain, which came in the form of the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act.

Tax credits for semiconductor firms rose under the OBBB from 25 percent to 35 percent. Such companies as Taiwan Semiconductor and Intel are eligible for the credits, provided they expand their manufacturing in the near future.

Taking advantage of onshoring

According to Foster, developers must remain agile and strategic in responding to emerging speculative trends, particularly as tenant interest shifts toward North American manufacturing.

“Markets—and submarkets—previously overlooked due to perceived lack of demand for industrial space may now be gaining renewed attention,” he continued. “These areas, better suited for manufacturing, could soon become focal points for development.”

With rising cost concerns and supply chain risks, businesses are becoming more strategic—prioritizing access to talent, modern facilities and geographic reach.

—Marie-France Benoit, Principal & Director of Market Intelligence, Avison Young Canada

Developers will also need to be forward-looking and focus on strategic industries like critical minerals, AI, clean energy and advanced manufacturing, which will influence the demand for industrial space and require specialized facilities and infrastructure, said Benoit.

“This is particularly true for industries heavily reliant on exports to the U.S. or those that rely on imports that may be subject to tariffs,” she noted. “This could lead to new opportunities in other markets, potentially impacting the location and type of industrial space needed in Canada.”

As for the competition among North American markets for new manufacturing space, those that already have strong manufacturing bases have the advantage when it comes to further development.

“Those markets that have the available employment markets for skilled manufacturing will do better,” Morris says. “I’m generalizing, but there’s a skill base that’s required. Another thing to think about in today’s market is an interest in foreign direct investment.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.