Self Storage Shakeout Ahead?

The sector’s strengths attract both REITS and private capital, yet some insiders worry about overbuilding and downward pressure on rental rates.

By Nancy Crotti

U-Haul purchased and rebranded these The Vault self-storage facilities in Menomonee Falls and in Waukesha, Wisc., respectively, in April 2017 for $17.08 million. The Mele Group of Marcus & Millichap, Tampa, Fla., represented the private-investor sellers in this record-breaking self-storage portfolio transaction for the Milwaukee MSA. A later expansion brought the Menomonee Falls property to 80,230 net rentable square feet and 768 units. The Waukesha store has 64,648 net rentable square feet in 582 units.

Private investors who once avoided dedicating precious time to midsize deals are now embracing an asset category where the prices are modest and public REITs have long dominated. Self storage offers low upkeep costs and opportunities for rent increases that are generally more frequent than in most other asset categories.

“Some people have come to the realization that it is what it is, and they still got into the industry,” said Rick Schontz, the founder of 18-month-old City Line Capital. A former self storage broker, Schontz partnered with a New York investment bank to start his Philadelphia-based firm. His typical clients are individuals who each invest some $10 million; that capital is allocated to multiple properties.

A REIT sponsored by SmartStop Asset Management recently acquired this 640-unit storage facility in North Las Vegas, Nev.

City Line owns 33 properties around the country, a number likely to reach 50 by end of the year, Schontz estimated. Most are managed by Storage Asset Management under the Storage Sense brand, the rest by Cube Smart. “We’re buying existing self storage operating companies and just rebranding them and changing the systems,” Schontz explained. “We’re looking at it as more of a cash-flow and longer-term hold. The larger part of the market right now is looking at construction and also doing conversions.”

Crow Holdings entered self storage in 2014, recognizing the value of a product that serves people at times of upheaval or transition, noted Nathan Bennett, a vice president in the Dallas-based company’s self storage group. The company concluded that the sector had weathered the Great Recession well and tends to be less risky than traditional real estate. “There are smaller equity checks, so we can diversify our risk by doing a bunch of smaller investments, so our fund is composed of 50 deals versus 20,” Bennett said. “No one investment can sink the fund if it goes bad.”

Like more established funds, Crow focuses on the top 30 to 40 U.S. markets, with properties in California, Texas, the Pacific Northwest and Florida. The company exited Denver but might re-enter that market, and is also eyeing Chicago. “The secret’s kind of out about storage now,” Bennett said. “It’s a good business. It has been for us so far.”

Heading to Smaller Markets

Some institutional investors have been priced out of the top metros by land and construction costs and are heading to secondary and tertiary markets, noted Luke Elliott, first vice president investments & director with Marcus & Millichap’s National Storage Group in Tampa, Fla. “Some of those markets, because of the new projects coming on, are definitely coming close to saturation from the market perspective,” he said.

Located in Chula Vista, Calif., this 900-unit property is a recent acquisition by a SmartStop Asset Management-sponsored REIT.

Yet demand among certain segments remains strong. Millennials with small apartments continue to fill units in markets like Austin, Texas; Charlotte; Denver; Nashville; Portland, Ore.; Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; and Seattle. Downsizing or relocating Baby Boomers are stashing their treasures in storage space in Las Vegas, Orlando, Phoenix and San Diego.

Pressure on rents has escalated in those cities. Street rates are down 5 to 8 percent this year, noted David Dent, senior real estate market analyst for Yardi Systems. Concessions have become more common to attract individual and small-business customers. Nationwide, rents dropped 3 percent year over year in June after falling 1 percent in April and and 2 percent in May.

The mix of customers is changing, too. Younger people, affluent people and women are gravitating to self-storage for reasons as diverse as the availability of climate control and improved security. “That’s why you’re seeing this trend toward interior corridors,” Dent said. “People feel more secure with interior corridors and there are cameras monitoring all activity on-site, so it gives people a sense of comfort.”

A SmartStop Self Storage-brand property in Texas City, Texas. (Image courtesy of SmartStop Asset Management)

For their part, well-off customers tend to tolerate rent increases that are more frequent and higher than those in other property categories. “These are affluent people who can afford it and don’t care,” Dent said.

Even with all the changes in the industry, the largest owners remain on top in terms of square footage. Five are public REITS, led by Public Storage, which had direct and indirect ownership in 2,402 self-storage facilities totaling 160 million net rentable square feet in 38 states as of June 30. Public also has part ownership of about 12 million square feet of storage in Europe and 29 million square feet of commercial self-storage in the U.S. Rounding out the top public REITs is five-year-old National Storage Affiliates Trust, which had 34 million square feet in 29 states at midyear. The only non-REIT among the largest owners is U-Haul, which has 55.2 million square feet in 49 states and 10 Canadian provinces.

Mom-and-Pops’ Staying Power

Despite the scale of their holdings, the big companies will never completely swallow up the mom-and-pop shops scattered across the country, contends Connie Neville, managing director & co-chair of SVN’s Self Storage Product Council. “It’s a very fragmented industry, but it was built by mom-and-pops and entrepreneurs,” said Neville, who specializes in New England deals. “Yes, some of them are being acquired and purchased by the big operators, but the big operators don’t want them unless they’re of a certain size.” Most major players eschew any property that has fewer than 80,000 people within a five-mile radius, Neville explained.

City Line Capital purchased this store in Chattanooga, Tenn. in March 2018 for an undisclosed sum. It has 50,829 net rentable square feet in 344 units.

Moreover, small independent owners typically refuse lowball offers out of pride, observed Wayne Johnson, chief investment officer with SmartStop Asset Management, which sponsors three public, non-traded self storage REITs. As of August, the company owned 118 assets comprising 8.7 million square feet in the U.S. and Toronto. “Everybody’s chasing deals and trying to place money and get it out,” Johnson reported. “It’s hard to place money. We can find all the storage we want to buy. The trick is finding the storage we want to buy at the right price. We have to look at a lot of deals.”

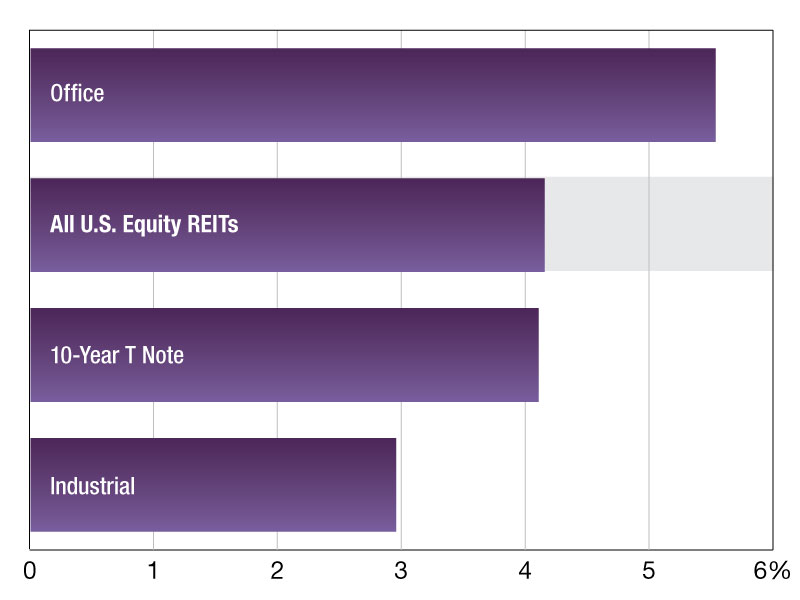

Looking at the larger picture, some self storage professionals see looming challenges on the horizon. With lease-ups taking longer, capital and construction costs rising and cap rates ticking up, an industry shakeout is ahead, predicted Bill Bellomy, co-founder & principal at Bellomy & Co., an Austin-based brokerage. “Those are pretty significant headwinds facing developers of storage,” he said. “For certain developers in certain markets, that’s going to be a perfect storm.”

Bellomy believes a that storm might be a year away, and expects its impact to vary widely: “I think it’s going to create some pain for some people but really good opportunity for others.”

You’ll find more on this topic in the September 2018 issue of CPE.

You must be logged in to post a comment.