No Joke. It Really Is Different This Time … Right?

Today, eight years into a slow-moving recovery in which commercial real estate has outperformed most every other investment class, the discussion is moving from whether the sector is overdue for a correction to how long the recovery will run and whether the industry has finally learned the lessons of past mistakes.

By Paul Fiorilla

Saying “it’s different this time” has long been a surefire way to elicit a laugh with an audience of commercial real estate professionals.

Saying “it’s different this time” has long been a surefire way to elicit a laugh with an audience of commercial real estate professionals.

After all, there are few things more certain than the cyclicality of the industry. Many of today’s leaders cut their teeth by finding profit in the S&L crisis in the early 1990s. So ingrained are cycles that a common way of denoting time is to reference the series of busts that follow the booms—the Russian bond crisis, 9/11, the global financial crisis, etc.

Today, eight years into a slow-moving recovery in which commercial real estate has outperformed most every other investment class, the discussion is moving from whether the sector is overdue for a correction to how long the recovery will run and whether the industry has finally learned the lessons of past mistakes.

“This market has beaten the pessimism out of me,” the noted bear Richard Jones, a lawyer at Dechert, said during a panel at the recent Commercial Real Estate Finance Council’s January 2018 Investors Conference.

Jones elaborated in a post on Dechert’s “Crunched Credit” blog: “I give up. I simply can’t see anything that will knock the continued growth of our economy, and hence, the continued health of the commercial real estate industry and the capital markets, off its current path. It’s hard to see how this party ends any time soon, and if someone at CREFC breaks into a rendition of ‘A Cockeyed Optimist’ from South Pacific, I’m not gonna smirk.”

Solid Fundamentals, Restrained Behavior

Optimism is based on several factors:

- The continued strong economy, which should be boosted by tax reform that was extremely kind to the president’s profession.

- Property fundamentals that generally fall between positive and robust.

- Continued strong capital flows that enhance liquidity and support record-high property values, while low acquisition yields seem immune from the slow rise in long-term interest rates.

- Perhaps most important, the uncharacteristic restraint exercised by the market this deep into a recovery.

The market’s discipline is the foundation for those who dare to wonder if today’s cycle is different from those in the past. Cycles don’t normally last this long, and typically after a few years with good returns the market starts to overheat. Construction is overextended, capital flows prompt equity players to chase ever-riskier deals that rely on unrealistic income assumptions, and hot competition pushes banks to be more aggressive in lending, increasing leverage and cutting coupons.

As we start 2018, however, the red flags normally associated with the late cycle are the exception rather than the rule. Construction has slowly picked up, but still can’t be said to be as irrationally exuberant as past cycles. Multifamily deliveries are expected to hit a cycle peak in 2018 (Yardi Matrix forecasts 360,000, up 20 percent over 2017), but at the same time demand and occupancies are strong in major markets. Metros with the heaviest pipelines will see rent growth level, or even shrink slightly, but that’s far from a crisis.

Other property types have similar dynamics. Construction is also strong in industrial and hotels. Industrial, though, is in the early stages of a logistics revolution and that necessitates the addition of modern stock in non-traditional locations. Hotels will feel the impact, though occupancy rates and revenue per available room (RevPAR) have been above-trend since 2010 as consumers allot more of their income to experiences over items such as clothing. Office construction is growing, though focused on major metros, so the impact will be limited. Retail construction is very weak, and focused on centers that are pre-leased.

Transaction volume hit a cycle peak in 2015, and has dropped roughly 10 percent in each of the last two years as buyers become more cautious. The bid-ask spread is growing, and more investors are searching for value-add assets rather than continuing to bid up prices in core markets.

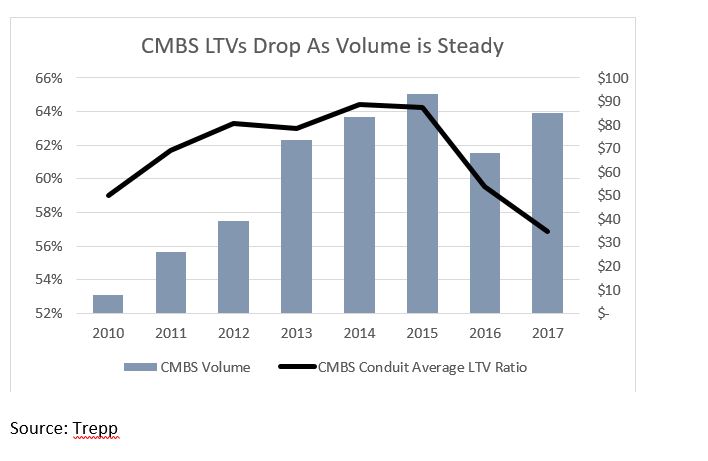

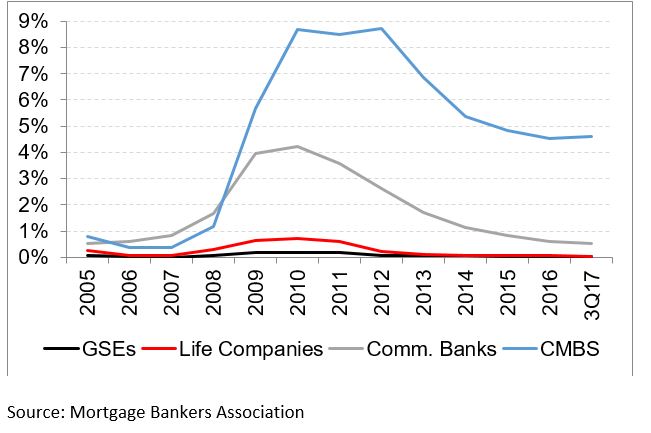

Likewise, lender behavior is restrained. CMBS issuer loan-to-value (LTV) ratios have declined for two straight years. After reaching a cycle high of 64 percent in 2015, they fell to just under 60 percent in 2016 and 57 percent in 2017. CMBS delinquencies, which soared in the wake of the last downturn, have been almost non-existent in “CMBS 2.0.” The default rate for loans securitized since 2010 is less than 1 percent. Delinquencies of loans originated by life companies and GSEs are minuscule, and banks are also below 1 percent.

Construction debt has become harder to get as large banks cut back in favor of permanent loans. Regional and local banks and alternative lenders such as private equity and sovereign wealth funds are grabbing an increased share, and even those lenders require borrowers to sink more capital into deals.

Regulatory Restraints

What’s driving the more responsible behavior? Some contend that Dodd-Frank and other regulations imposed in recent years are the driving factor, while others say the market has become smarter. The answer is probably a bit of both.

CMBS has been fundamentally changed by regulations, including the requirement that bank executives personally certify the loans in pools, and risk retention, which went into effect in December 2016 and requires issuers of CMBS deals to hold or sell to a qualified “B-piece” buyer a 5 percent strip. Some were predicting those and other rules would derail the market, but issuance reached $95.3 billion in 2017, up from $76.0 billion in 2016, according to “Commercial Mortgage Alert,” and issuer profits soared.

Because the holders of the retained bonds can’t sell them for five years, they have a larger stake to ensure that loans don’t default, contributing to an uptick in quality. Contrast that to the last cycle, when the buyers of junior bonds repackaged them into collateralized debt obligations and essentially sold the risk to (largely unsuspecting) third parties.

Regulations do have repercussions. Risk retention tilted the field toward large banks that have the inclination and the means to retain bonds, so smaller securitization programs have been dropping out. Regulatory efforts such as the Volker Rule that hamper banks’ ability to retain bonds on their books have reduced liquidity to the point where there is a limited number of buyers for triple-A rated CMBS classes.

In the past, triple-A bonds, which constitute roughly 80 percent of the transactions, were purchased by a wide range of investors. However, short-term holders such as money managers and hedge funds have largely stopped buying, in part because investment banks no longer finance bond purchases. The pool of buy-and-hold investors is sufficiently small to limit most CMBS deals to $1 billion, or about $800 million of triple-A classes. That gives senior bond investors a larger say in the composition of pools (even if it is mostly indirect), since issuers know that deals that fail to attract triple-A buyers will be unsuccessful.

Data Revolution

That regulatory efforts have constrained behavior doesn’t mean that the market also hasn’t learned from its mistakes. “A lot of banks have a lot of discipline and are being conservative of their own volition,” Jeffrey Fastov, a senior principal at Square Mile Capital Management, a New York-based alternative lender, said on a panel at the CREFC conference.

Many industry professionals lost jobs and/or income after the last crisis, and entire companies and business platforms were wiped out, an experience that nobody wants to repeat. What’s more, the market benefits from the proliferation of data that improves the ability to make sound decisions. Increasingly sophisticated data tools enable lenders and developers to keep track of supply and demand down to the submarket level, making it easier to delay or reject projects that might not pencil out. It is easier today for buyers to analyze comparable property sales, which helps to avoid overpaying for an asset. Lenders have an increasing number of analytical tools that helps to determine how to structure good loans.

The data revolution remains at its beginning stage, and those who argue that real estate has yet to fully embrace the implications have a point. Data also is no substitute for sound judgment—it provides history, but in the end people must decide what that means for future performance. Even with those caveats, more information is available to the market in this cycle, and doubtless has had a positive effect on decision-making. Lenders can see what failed in the last cycle and avoid loans with those types of terms.

Economy Rules

Effective regulation and good decision-making are great, and will mitigate the harm done by downturns. In the end, though, nothing is more important to the market than the performance of the economy. The signs in 2018 are positive: Job creation remains healthy, GDP has picked up in recent quarters, and tax cuts should provide a stimulus.

Headwinds such as the growing federal budget deficit and rising interest rates appear to be longer-term problems that will present themselves in 2019 or later. The economy does not appear to be overheated in any individual segment and the consensus is that the main threat is an exogenous event, which of course are impossible to spot in advance.

One could argue that the commercial real estate market hasn’t been this optimistic since just before the last downturn, a point made by Fastov, who said: “Every time it feels like it’s different, that usually precedes a disaster.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.