What the Senate Version of the Big Beautiful Bill Means for CRE

On bonus depreciation, the Senate went even further than the House did.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed by the Senate yesterday largely assuages commercial real estate professionals. The measure, which now returns to the House for a vote or more amendments, maintains current law on policies that tend to come under the magnifying glass every so often, including business property and income tax deductibility, carried interest and Section 1031 exchanges.

Both the Senate and House versions proposed some changes to the tax code that would benefit CRE, including improvements to the Opportunity Zone and Low-Income Housing Tax Credit programs. Meanwhile, property or business investors stand to benefit from a proposal that would shield more qualified business income received individually or through pass-through structures like partnerships, S corporations, trusts and REITs. The Senate version would leave the potential deduction for qualified business income at 20 percent but make it permanent. The House had voted to raise it from 20 percent to 23 percent.

“That’s a possible benefit that not a lot of people are talking about, as most real estate is held in LLCs,” observed Andrew Sinclair, CEO & principal of Midloch Investment Partners, following the passage of the House version.

Both the Senate and House voted to increase the SALT cap to 40 percent. But the Senate version preserves the deduction for certain pass-through businesses, according to the Journal of Accountancy. The House version would have disallowed some partnerships from taking a deduction for sales taxes at the local and state level as well as income and property taxes.

“It’s definitely a political football,” said Sinclair of the House bill. “It could create some problems for landlords.”

Fortunately for CRE, Provision 899, which would have allowed the U.S. Treasury to impose annual tax increases of 5 percent on direct investment in the U.S. by foreign investors, has been permanently removed from the bill.

The provision was in response to tax policies in other countries considered to be unfair to the U.S. Ultimately, the retaliatory tax would have been capped at 20 percent unless the perceived unfair tax is removed by the offending country. The Real Estate Roundtable along with other industry groups lobbied hard for the provision to be eliminated from the bill, or at least revised.

The bill also has many of the renewable energy incentives contained in the Inflation Reduction Act sunsetting earlier than written, and it adds an extra tax on wind and solar projects if a certain percentage of materials are sourced from prohibited countries, like China.

Full bonus is back

The Senate version reinstates bonus depreciation for properties placed in service after Jan. 1, 2025, and makes it permanent for short-lived projects. The House had moved to temporarily reinstate 100 percent bonus depreciation retroactive to Jan. 1, 2025. That policy was first enacted in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 during the first Trump administration.

The provision would allow businesses to fully deduct the cost of certain machinery, equipment, building improvements and other eligible assets the year they’re placed into service.

“Bonus depreciation was one of the best features about the original 2017 act because it helps to spur capital formation, which encourages activities like building new factories,” noted Timothy Savage, a clinical assistant professor at the Schack Institute of Real Estate in New York University’s School of Professional Studies.

Under current law, bonus depreciation has been declining each year—it’s 40 percent for 2025 and is set to phase out after 2026. To qualify for bonus depreciation under the current proposal, developers must break ground on a facility before 2029 and place it into operation by the beginning of 2031, according to the Tax Foundation’s interpretation of the Senate’s action.

The return of bonus depreciation could alter the landscape of manufacturing even more dramatically by incentivizing new automated production facilities in the U.S., suggested Peter Kroner, director of industrial market intelligence with Avison Young. That’s largely because offshoring years ago took advantage of cheap labor, which isn’t necessarily the case with automation.

By extension, reshored facilities could create a center of gravity as vendors in the supply chain move closer to producers, he added. In its latest industrial report, the brokerage firm noted that manufacturing investments of more than $2.75 trillion had been announced in the U.S. since the beginning of 2025.

“The provision is a catalyst—it’s going to lead some companies to reshore to the U.S.,” commented Kroner. “And it could happen in a flurry because I think it’s been flying under the radar.”

OZ rescripted

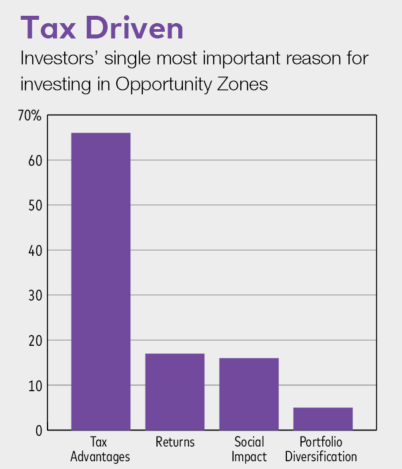

Property investors are just as focused on the fate of proposals to extend the OZ program amid other changes. Considering that many OZ projects were delayed by a slow rule-making process, the pandemic’s disruption of supply chains and a spike in interest rates, industry advocates hoped to convince senators to extend the original deferral period to the end of 2028 at the earliest.

Both Senate and House versions breathe new life into the program, but the Senate version would reauthorize the OZ program on a rolling 10-year basis starting in 2027, according to EY.

Enacted as part of the TCJA, the program allows investors to roll profits from stocks, bonds, properties and other assets into real estate and businesses located in 8,700 disinvested census tracts.

The investments are made through qualified opportunity funds set up specifically for this purpose, which in turn provide investors with a capital gains tax deferral on those profits through 2026 and a complete tax exemption on the QOF gains if the investment is held for 10 years. Given the upcoming deferral deadline, however, the incentive was becoming less attractive.

Under the bill passed by the House, a new capital gains deferral period would be established with a deadline of Dec. 31, 2033. But that would be available only to investors who funnel gains into a QOF beginning in 2027. Those who invested in QOFs in the program’s original iteration would still see their deferral end in 2026.

“I think the OZ community is underwhelmed by what the House has passed,” said Blake Christian, a tax partner with HCVT in Park City, Utah, who leads the firm’s OZ consulting efforts. “We were expecting a little bit more. But then again, we’re also relieved that we’ve got an extension that keeps the program alive.”

Bonus depreciation was one of the best features about the original 2017 act because it helps to spur capital formation, which encourages activities like building new factories.

—Timothy Savage, Clinical Assistant Professor, NYU Schack Institute of Real Estate

Map rearrangement

The proposal to largely redraw the map of census tracts eligible for OZ funding is another key area of focus for real estate investors. New income parameters, for example, seek to address past criticism that some OZs weren’t really starved for investment, and the number of OZs is expected to drop by 25 percent, to 6,500.

Both versions would exclude designation of contiguous non-low-income census tracts. But the Senate version excluded the House’s requirement that 30 percent of a state’s OZs be in rural communities.

The map revisions could shore up the program and provide communities with a better understanding of how it works, suggested Primestor Development CEO Arturo Sneider during a tax policy panel discussion at the recent ICSC Las Vegas retail real estate convention. The first round of “Opportunity Zone mapping was done very, very fast,” noted Sneider, whose firm concentrates on urban infill projects and who is also chair of ICSC’s political action committee. “I think many jurisdictions missed the boat completely.”

Shifting priorities

In other changes to OZs, the Senate and House agreed on providing a 30 percent step-up in basis on gains rolled into a QOF that invests in rural areas and 10 percent on gains sunk into a non-rural QOF if the investments are held for five years before the end of 2033.

That echoes a temporary and now-unavailable provision in the original OZ program that provided a step-up in basis of up to 25 percent on the gains.

Further, both parties voted to lower the “substantial improvement” requirement for rural QOFs. Currently, funds need to invest the amount of capital to improve a building that is equal to its value at acquisition. The House bill’s provision would cut that required capital investment to 50 percent of the value.

“We have a lot of clients who are in the multifamily rehab market, and you could never spend enough per unit to reach the 100 percent basis increase,” said Christian. “But for a major rehab, a 50 percent target is within range.”

Finally, both versions of the bill call for more QOF reporting and transparency in order to better monitor the program’s success. As with questions over whether certain OZs were truly distressed, the lack of oversight has received repeated criticism.

You must be logged in to post a comment.