Flipping the Script

Merle Gross-Ginsburg is a seminal figure in the advancement of women in commercial real estate. Trading her native Galveston, Texas, for Manhattan’s Upper West Side, she set out to rehabilitate the neighborhood, and in the process, became the first person to create a brownstone co-op in New York City. A pioneering property manager and brokerage professional, she launched AREW, the first organization for women real estate professionals, in 1978. Now retired, she continues her advocacy.

By Sanyu Kyeyune

Merle Gross-Ginsburg is a seminal figure in the advancement of women in commercial real estate. Trading her native Galveston, Texas, for Manhattan’s Upper West Side, she set out to rehabilitate the neighborhood, and in the process, became the first person to create a brownstone co-op in New York City. A pioneering property manager and brokerage professional, she launched AREW, the first organization for women real estate professionals, in 1978. Now retired, she continues her advocacy.

“The fields that were open to women in those days, if you were ‘not fortunate enough to get married,’ were nursing and teaching,” Merle Gross-Ginsburg recalls of her formative years in the 1950s. “Being an airline stewardess was just coming into vogue, but you had to be five-foot-four to do that, so it was clearly out of the question for me,” joked the longtime New York City-based broker, who stands about five feet even. “Even though I tried to do pull-ups.”

As it turned out, the spirited young woman from Texas was destined to follow a far less ordinary flight path. As a practitioner, she was a pioneering property manager, broker and entrepreneur. And as the founding president of the Association of Real Estate Women, she has contributed greatly to the advancement of women in the industry.

“Merle’s success is a result of her single-minded dedication; her intelligence, laser focus and ability to identify needs and then create opportunities,” said her friend Diane Diamondstein, a retired Chase Manhattan Bank executive whose career was boosted by AREW.

At first, Gross-Ginsburg’s future appeared to be more characteristic of mid-century, middle-class America. Eyeing a career as an historian, the Rice University graduate traveled to Cambridge, Mass., to take summer courses (and partly to escape a star-crossed engagement). While in Cambridge, she met a recent Harvard graduate named Bernard Gross; the two married three days before Merle’s 21st birthday.

The couple took up residence in a starter apartment near Newark, N.J., but found themselves rather stifled by suburban life. The Grosses found a place on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, and while Bernard juggled a full-time job and graduate school at Columbia University, Merle enrolled in an executive training program at Bloomingdale’s. She cut her training short, however, when she learned she was pregnant. Aside from her own mother, widowed when Merle was 10, she knew no examples of working matriarchs.

“Betty Friedan had not yet written The Feminine Mystique. Gloria Steinem and Letty Pogrebin had not yet established the Ms. Foundation (for Women). So there was not a lot of support for women working,” she recalled. “If you were single and working, it was only to make enough money to support yourself until you got married, and then, only until your husband could support the family.”

Tidying the block

Following a stroll in Central Park one afternoon, Gross-Ginsburg visited a neighbor who took in boarders at her brownstone home. Gross-Ginsburg returned home and suggested to her husband that they make a go of running their own establishment. Pooling their wedding gifts, small loans from their parents and a promissory note, they bought a brownstone at 135 W. 77th St. for $47,500, making a $12,000 down payment.

Following a stroll in Central Park one afternoon, Gross-Ginsburg visited a neighbor who took in boarders at her brownstone home. Gross-Ginsburg returned home and suggested to her husband that they make a go of running their own establishment. Pooling their wedding gifts, small loans from their parents and a promissory note, they bought a brownstone at 135 W. 77th St. for $47,500, making a $12,000 down payment.

They took two rooms for themselves and rented out the rest for $10 to $15 per week (linens and cleaning service included). Most customers were single men. Of that early venture, Gross-Ginsburg recalled, “I had been so imbued with this fantasy of what I was going to be able to do that I really did not look realistically at the surroundings.”

The Upper West Side of the 1960s showed hardly a glimmer of the hip affluence it would later assume. “We lived on one of the top dope-drop blocks, notorious with drug dealers,” she described. “There was one single-family house left on the block, two public schools, and the rest were mostly rooming houses.” The latter establishments attracted a clientele of dubious character.

Gross-Ginsburg heard from an acquaintance about an urban renewal incentive program sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Despite the availability of tax abatements for rent-stabilized buildings, most banks would not lend on an Upper West Side property.

Determined to spruce up her surroundings, Gross-Ginsburg invited a friend to team up with her on the conversion of a residential property. “I put in the sweat, and she put in the money,” she explained. “And that’s how I got into real estate.”

Learning on the job

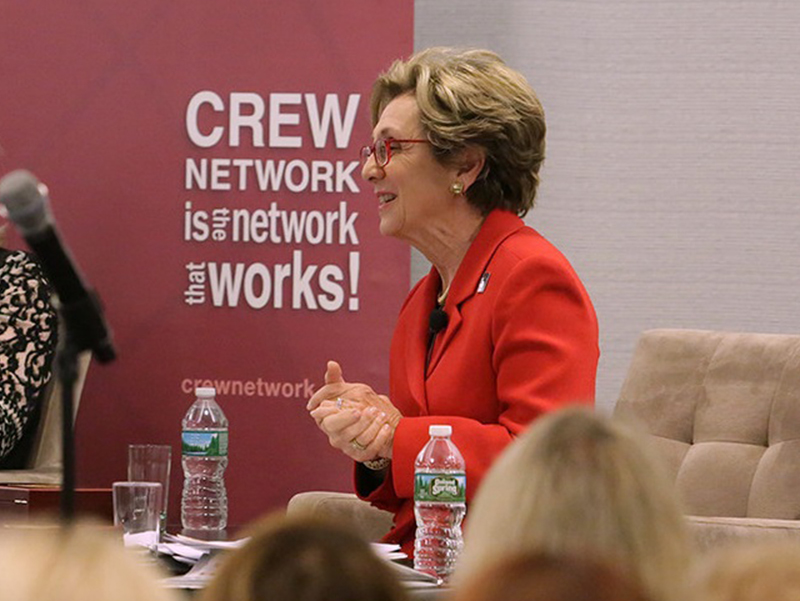

Gross-Ginsburg addresses the audience at CREW New York’s Fall Leadership Summit in October 2016.

Gross-Ginsburg bought four rooming houses and turned them into co-ops. Serving as her own contractor, she learned the nuts and bolts of building management. When an interest-rate spike forced her out of the renovation business, she took a job sorting listings at a small brokerage shop.

In 1974, she moved on to a part-time assistant role in the leasing and management company founded by Edward S. Gordon. Her schedule initially gave her time to spend with her children, but other factors intervened: Her marriage was ending, and the company was prospering. Within a year, she was piloting the firm’s budding building management business, which handled 450 Park Ave., a 32-story Midtown Manhattan office tower.

The job proved to be a natural fit. Where building engineers would give up, Gross-Ginsburg relished the challenge. “If I was given a problem, I figured out how to solve it,” she explained. “Since I’d been around some construction, I somehow wasn’t afraid of it.” Wending her way through the building’s interior, she would track down the source of vexing mechanical issues. Once she even gained entry to the basement of an adjacent property to find the source of a perennial leak.

Gross-Ginsburg led the successful renovation and management of the Chrysler Building, prompting Gordon to offer her a stake in the business in 1978. That gave her the distinction of being the first woman to make partner in a New York City real estate firm without being a family member. But the milestone had a downside: Gordon politely dismissed her from the property management job she loved, explaining that a male in the position would be better for appearances.

Coalition building

After switching to Edward S. Gordon’s leasing and sales practice—which lacked the thrill of building management—Gross-Ginsburg felt emboldened to try joining the Young Men’s Real Estate Association. However, she was turned away under a charter provision that prohibited membership by women. Tagging along with Gordon to a dinner held by the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), Gross-Ginsburg counted exactly two other women professionals alongside 1,800 cigar-puffing men: Peggy Carnegie, a prominent investment sales broker, and Leona Helmsley, who was then a broker before achieving fame as a hotel magnate in partnership with her husband, the investor and manager Harry Helmsley.

Perhaps forseeing a tidal shift, REBNY asked Gross-Ginsburg and seven others to head a seminar titled “Women in Real Estate Who Have Made It.” The event drew about 100 women, she recounted, “and none of us knew each other.” That sense of isolation underscored the lack of opportunity for networking and mentorship among women. Gross-Ginsburg resolved to create an organization that would fill the gap.

She first approached a speaker from the REBNY panel and two fellow students from New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate, where she had been taking evening courses. They turned her down flat, insisting that they were too busy or had fought too hard to help others succeed.

Characteristically, Gross-Ginsburg soldiered on, and found a more receptive group of women to start an association. To achieve legitimacy, the group initially called itself the Women’s Committee of the Real Estate Board of New York. “Her tenacity brought together a bright group of relatively young women,” recalled Marilyn Weitzman, managing principal of The Weitzman Group and an original AREW board member.

During AREW’s first year, the women developed the committee’s structure, modeling its bylaws after REBNY’s. They held monthly luncheons showcasing industry leaders. Mining the expertise of its members, the group published a newsletter and led workshops on finance, management and sales.

Making a name

In fall 1978, under its new name—Association of Real Estate Women—the group held its first luncheon, themed “Opportunities for Women in Real Estate.” The event drew an audience of 175 and featured four prominent male executives. In addition, Weitzman led a popular seminar on entrepreneurship. At later events, members gained leadership skills and public speaking experience, and were encouraged to take continuing-education courses in their specialties.

By the early 1980s, the organization was gaining traction. On Aug. 2, 1981, the cover of The New York Times’ real estate section featured an article titled “Slowly, Women Progress in Commercial Brokerage.”

The experience of Gross-Ginsburg’s friend Diane Diamondstein illustrates the crucial role AREW has played. A meeting with a former colleague at an AREW event opened the door to a long career at Chase Manhattan Bank. Access to AREW’s member directory fostered her advancement in the bank’s real estate valuation unit.

Gross-Ginsburg remained with Edward S. Gordon for the rest of her career, retiring in the early 1990s as a senior vice president, but her contributions continue to influence the industry. To coincide with its 30th anniversary in 2008, AREW established a scholarship in her name at New York University’s Schack Real Estate Institute. And in another milestone, AREW merged with New York Commercial Real Estate Women in 2014 to form CREW New York.

“Women are doing jobs today that you couldn’t dream about 30 years ago,” Gross-Ginsburg observed, reflecting on the changes she has done much to bring about. “AREW really helped accelerate that process. It achieved the goal of enabling professional women to operate equally with men, and to succeed.”

Originally appearing in the April 2017 issue of CPE.

You must be logged in to post a comment.