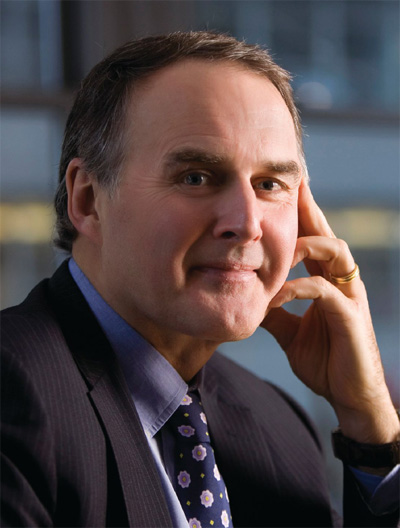

Change Agent: Confident & Congenial, Hugh Frater Re-Energizes Berkadia Commercial Mortgage

Known for his upbeat, approachable manner as well as for his 25 years in finance, Hugh Frater has brought welcome changes to Berkadia Commercial Mortgage, including a proprietary lending business, an expansion of the company’s own stable of lenders and a retooling of the executive team.

When Hugh Frater arrived at Berkadia Commercial Mortgage L.L.C. in August 2010, he had his work cut out for him. Despite the Horsham, Pa.-based company’s stature among the nation’s top loan servicing companies, the veteran finance executive found the firm to be troubled in ways that never showed up on its balance sheet. The greatest challenges he found were intangible. “Berkadia and its predecessors had had a pretty rough ride,” he explained last month in the company’s New York City office, where he works several days a week.

During the previous four years, Berkadia’s people had endured a punishing recession, two transitions to new ownership and multiple management changes. Berkadia had been formed in December 2009 by a joint venture of Berkshire Hathaway and Leucadia National Corp., which had purchased the North American loan servicing business of Capmark Financial Group Inc., the one-time GMAC Commercial Mortgage Corp.

That sale was the endgame of Capmark’s inability to bounce back from the economic downturn. “A lot of the effort of the last two years has been to strip away that baggage,” Frater explained, and to restore vital qualities that had fallen to a low ebb: “the sense of excitement, the sense of mission and the sense of fun at work.”

Known for his upbeat, approachable manner as well as for his 25 years in finance, Frater immediately went to work restoring the morale of shell-shocked team members. He traveled widely to Berkadia’s offices, listened to the concerns of management and rank-and-file, and enlisted his lieutenants to help spread his message of optimism and renewed commitment to best practices.

Frater’s knack for understanding the human side of any equation has contributed as much to his reputation as has his capital markets know-how. “I think Hugh combines a great deal of technical knowledge and understanding of how underlying markets and securities work with a great sense of people,” said J. Richard Kushel, senior managing director & head of BlackRock Inc.’s portfolio group, who worked with Frater at the firm from 1991 to 2004. “You talk to his clients, and they are incredibly loyal to him because he talks to them and understands them. I think that’s true of the people who work for him.”

Fast forward to 2012. During his relatively brief time at the helm, Frater has inaugurated a proprietary lending business, expanded the company’s own stable of lenders and retooled the executive team. Meanwhile, the company has firmed up its position among the nation’s most active mortgage banking firms. Last August, the Mortgage Bankers Association ranked Berkadia among the industry leaders in a wide range of primary and master servicing categories: third in overall loan portfolio ($184.2 billion), third in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loans ($27 billion), fifth in special servicing ($28 billion) and in the top 10 in multiple other categories. The company came in at No. 10 on the association’s last originations ranking, with $4.6 billion in volume in 2010; for the CPE-MHN Most Powerful Mortgage Banks ranking, it reported $5 billion for the year ending Sept. 30, 2011. (It placed 18th on the CPE-MHN ranking, which evaluates innovation and breadth in lending rather than strictly volume.)

Berkadia’s two-year-old ownership by the Berkshire Hathaway-Leucadia joint venture is predictably proving to be a competitive advantage. Being identified as part of the empire led by Warren Buffett confers credibility with the government-sponsored enterprises, investors and clients. As Frater puts it, “No one asks if we’ve got the money.” Such indicators speak for themselves, yet an equally important achievement is impossible to measure. “If you asked the people (working at Berkadia) a year ago how do they feel and asked them today, it’s probably night and day,” Frater said.

Having guided the company’s internal turnaround, Frater is sifting carefully through often contradictory signals as he maps out Berkadia’s future. On the plus side, he said, the payoff rate for maturing loans in the company portfolio improved dramatically year-over-year in 2011. He cites Berkadia’s Boston portfolio. Only about 30 percent of loans that came due in 2010 were paid off, but that number hit 75 percent in 2011. That is encouraging news, to be sure, yet Frater remains skeptical that happy days are here again. Keeping an eye on week-to-week changes in loan payoff rates reveals volatility and suggests a more nuanced view.

Frater also regards the refinancing issue with deep concern, noting the “very, very substantial gap between the amount of capital needed and the amount available.” Even the most optimistic projections for new CMBS securitizations in 2012 fall far short of generating the proceeds necessary to refinance loans maturing this year. Commercial banks, life insurers and other lenders may be willing to increase their allocations to some extent, but they will be hard-pressed to bridge the gap left by the shortfall in CMBS financing. The problem will only grow as 10-year loans made during the market’s peak begin to mature in large numbers around 2015. Frater has managed through numerous cycles and is hardly an alarmist, yet he states, “I think we have a potential disaster on our hands.”

Disquieting as that prospect is, Frater also maintains that it presents an opportunity for Berkadia to step up. “Uncertainty is generally good for us,” he said. “It means that our fundamental constituencies—our borrower clients and our investor clients—need us more.” Frater’s charge is to ensure that Berkadia can continue to fulfill that long-time role. The company’s roots stretch back to 1994, when it was founded as GMAC Commercial Mortgage Corp. In March 2006, the company was acquired for $1.5 billion by a joint venture of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., Five Mile Partners L.L.C. and Goldman Sachs Capital Partners. The new ownership re-branded the company as Capmark Financial Group Inc. and brought in a new executive team.

But like so many other real estate finance players, Capmark ran aground during the recession. During the third quarter of 2009 alone, the company posted a loss of $1.6 billion. Capmark began talking with potential suitors, and on Sept. 2 of that year, it revealed an agreement to sell its North American loan business to the Berkshire Hathaway/Leucadia joint venture, whose $515 million offer edged out a bid from PNC Financial Services Group Inc. The transaction closed in early December 2009. In between those two milestones, on Oct. 25, Capmark filed for bankruptcy protection, emerging two years later, on Sept. 30, 2011.

As Frater views the commercial real estate landscape, he sees the multi-family area as a standout among the property sectors Berkadia serves. “What I’m taking confi dence in is that 17 million apartment units in the U.S. are not going away,” he said. “We don’t need less of them. If anything, we need more of them.” Demand outpaces supply in most markets, a trend which Frater argued cannot be consistently said of other property types.

The company’s sweet spot is the middle-market loan valued at between $5 million and $25 million. In January, for example, it originated a $13 million HUD/FHA refinancing for Stone Oak Care Center, a nursing home in San Antonio. That transaction replaced a bridge loan that had been placed by Capmark.

As generally robust as the multi-family market appears to be these days, Frater is mindful that the sector has its share of uncertainty, too. In the long run, the biggest moving parts surround the two government-sponsored enterprises. Speculation varies widely as to what a new Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would look like, but downsizing or phasing out the two troubled giants could drastically alter the multi-family finance landscape.

“If the agencies are not going to continue to be a significant supplier of capital, there’s a lot more risk than people think,” Frater contends. For starters, the resulting scarcity of capital would hike borrowing costs significantly. A decision on the future of the GSEs may not emerge for several years, but in the meantime, Frater’s strategy is intended to stand Berkadia in good stead no matter what Congress decides.

One new avenue is the debut of its proprietary lending business, which the company formally unveiled last March. Drawing on capital generated by Berkadia itself, the program is intended to fi ll a niche: the demand for financing by borrowers who find it difficult to secure other sources of capital. The new platform specializes in floating-rate bridge lending for borrowers seeking to reposition properties through non-recourse commercial debt. Frater explained that the liquidity of the permanent loan market for multi-family makes it the best fit for the new platform. Other property categories still tend to be considerably more susceptible to fluctuating consumer demand and changing labor markets. For that reason, he explained, Berkadia’s loan origination is “very, very selective once you get away from multi-family as an asset class.”

The program’s origination volume exceeded $300 million in 2011 and is projected to grow by at least 10 to 15 percent in 2012. Sample transactions closed during its fi rst year included a nearly complete project in Brooklyn, N.Y., that will encompass 113 rental units plus 6,000 square feet of retail. Berkadia’s New York City office refinanced the construction loan through a $28 million floating-rate transaction.

A proprietary lending program brings not only increased potential for growth but also increased exposure. To meet the need for a robust risk-management strategy, Frater brought in Morgan Stanley alumnus Luther Peacock in April 2011 to serve as chief risk officer, a new post. That appointment was one of several additions to Berkadia’s senior leadership. Randy Jenson, the firm’s president & CFO, joined in July from Ranch Holdings L.L.C., an investment management company he had co-founded.

Further expanding Berkadia’s access to capital has been another priority. Starting in late 2010, the company began a concerted effort to broaden its contacts in the life insurance business. All told, Berkadia projects life company originations valued at $1 billion in 2012. It has brought in additional mortgage bankers and support staff, which has enabled the firm to increase its network of life-company capital sources to about 25. Last September, Berkadia added a $2 billion servicing portfolio of life-company loans when it acquired Jacksonville, Fla.- based Tavernier Capital Partners L.L.C. Most recently, in December, Berkadia opened an office in Tempe, Ariz., that will focus on tapping into life companies.

Berkadia is also eyeing multiple regions for potential expansion across a variety of business lines: Atlanta and other Southeastern markets; Southern California; San Francisco; Phoenix; Portland; Seattle; and select markets in the nation’s North Central area.

At least one avenue to Berkadia’s growth has been less than welcoming, though. Turmoil in the real estate capital markets has caused contraction, and as a well-capitalized player, Berkadia has the resources to pull off strategic acquisitions. But fewer opportunities have arisen than Frater expected. “We’ve had a lot of conversations (with potential merger partners),” he reported, “but those talks have almost always been frustrating or inconclusive.” A rare exception, the Tavernier Capital acquisition last September was bolstered by a natural chemistry: Tavernier’s founders were alumni of Berkadia’s legacy firms, Capmark and GMAC, who had departed in 2007 over differences with Capmark’s leadership at the time.

While working to instill a renewed sense of confidence and mission, Frater has also promoted practices aimed at analyzing the company’s operations more effectively. “Another big change is … we’re measuring more and more things,” he said. As an example, he cited a new effort to track underwriting times. Monitoring how long it takes to reach each milestone in the process, from the initial application to the quote to the loan closing, allows for more accurate assessment of productivity and processes.

Learning the Ropes

On the way to his current position at Berkadia, Frater took a path that encompassed stops in media, investment banking and renewable energy, as well as the real estate capital markets. As Kushel, his former colleague at BlackRock, explained, “He hasn’t been afraid to reinvent himself.” Soon after graduating from Dartmouth College with a degree in English, he spent three years as programming director for The Learning Channel. In 1983, he entered Columbia Business School, where he explored his interest in fi nance.

Frater received an initial taste of investment banking between his fi rst and second years in graduate school, working for Goldman, Sachs & Co. as a summer associate in equity sales and trading. After receiving his M.B.A. in 1985, he was recruited to Lehman Brothers Inc. by Ralph Schlosstein. He spent the next three years in Lehman’s institutions and merger department, working on equity and debt financings and strategic transactions for mortgage lenders, homebuilders, savings institutions and banks.

“He was a very talented, hard-working professional who, despite the fact that he was extremely talented, didn’t let it go to his head,” Schlosstein recalled. In 1988, Schlosstein invited Frater to be a charter partner in a new enterprise: an investment management company dubbed Black- Rock Inc. During the next 15 years, Frater wore a variety of hats as Black- Rock grew into the world’s biggest investment manager.

Co-head of institutional client service and business development and a member of the management committee, he started a team that specialized in high-yield securities, mezzanine loans and preferred equity backed by commercial real estate, and launched Anthracite Capital Inc., a specialty finance company, as well as the Carbon Capital group of funds, which provide mezzanine lending through a series of private institutional commingled funds.

In February 2004, Frater moved to PNC Financial Services Inc., where he led the real estate fi nance division and served as CEO of Midland Loan Services, the bank’s commercial loan servicing unit. He managed a $200 billion loan servicing portfolio, $11 billion in debt commitments and $13 billion in lending volume annually. On Frater’s watch, lending volume, revenue and profi ts all rose upwards of 70 percent. He recalls it as “a fascinating experience because it was my fi rst large corporate experience.”

After 19 years in finance, much of it dedicated to commercial real estate, Frater branched out. In November 2007, he joined Good Energies Inc., an international, privately held investment management company focused on renewable energy. Taking on multiple roles as COO, managing director & senior advisor, Frater oversaw portfolio and risk management and served on the investment committee.

Among other accomplishments, he generated improvements in investment and portfolio reporting processes, trimmed operating expenses and led an initiative to rationalize the organizational structure. Fallout from the capital markets crisis caught up with the company, however, and in June 2010 Frater departed as part of a restructuring. The break turned out to be brief. As Frater was mulling his next move, Berkadia approached him, and by August he had signed on as CEO.

Regarding Frater’s personal demeanor, Schlosstein commented, “There are very few people that Hugh has encountered in his career and in his personal life that don’t enjoy being with him.” An executive with a reputation for congeniality, Frater strives to convey the message that he is approachable, no matter what the issue. Whether the setting is a committee meeting or an office-wide town hall, Frater says, the lines of communication are always open; he is game to address whatever concerns may come up. “I will not be offended,” he insisted, adding that “there is no such thing as a dumb question” is a favorite piece of advice.

For his part, Frater believes that congeniality is compatible with another quality he prizes: the judgment and confidence to disagree with the boss. Indeed, Frater says the highest praise he can bestow in a performance review is that the person is unafraid to challenge the boss’s thinking.

When Frater joined Berkadia, he followed a practice that has become habit at his last few jobs, pursuing an exercise suggested by Leon Kendall, former chairman of Mortgage Guaranty Insurance Corp. For the first 90 days on the new job, Kendall advised, “write down everything that comes into your head.”

The 90-day threshold is crucial because that is roughly how long it takes for a newcomer to become part of the team. So Frater opens up a new spiral-bound notebook and fills it with his ideas about the company and impressions of his new colleagues. “An important part of anything I’ve done is determining who’s truthful, who’s got integrity, who’s got energy,” he said.

During the initial stretch on any new job, an executive is absorbing a vast download of data. Frater is well aware that it can take even a seasoned executive some time to tell when somebody is trying to sell a bill of goods. Yet for Frater, the spiral notebook has also confi rmed the value of trusting first impressions. “What you write down in the first few weeks after you’ve been spending 15 hours a day talking to people is always right.”

Judging by Frater’s accomplishments so far at Berkadia, those instincts are giving him a high batting average.

You must be logged in to post a comment.