At Long Last, a Measure of Mezzanine Loans

Investors in high-yield real estate now have a way to compare their returns and performance against an industry-standard benchmark, thanks to John B. Levy & Co.'s creation of the first mezzanine loan index.

By Paul Fiorilla

Indexes proliferate in financial markets as a way for investors to benchmark investment strategies and manager performance. The commercial real estate market is no different, as there are multiple indexes that measure the performance of public and private real estate, property types, different geographies and investor strategy.

One key exception, however, has been mezzanine debt, an investment type that grew substantially during the last cycle. Mezzanine loans are difficult to measure, in large part because each is relatively unique and most investors are private entities that are loathe to share performance information.

Now, however, the market has its first mezzanine loan index, created by John B. Levy & Co., which has been publishing a quarterly performance index for senior debt (the Gilberto-Levy Index) since 1993. The new Giliberto‐Levy High‐Yield Real Estate Debt Index, is the first third‐party measure of high‐yield commercial mortgage debt performance. Both indices were co‐created by John Levy, president of the firm, and investment manager Michael Giliberto.

“Investors in high‐yield real estate have long wanted to compare their returns and performance against an industry-standard benchmark,” said Levy. “Our G‐L 2 carefully crunches the numbers and variables within financing packages, giving high‐yield investors the deep insight that was previously only available to holders of senior loans.”

Investors Seek Benchmark

Mezzanine debt investors have long craved a high-yield debt index to create a barometer of performance and guidance for price quotes for deals. Having an index generally improves liquidity in a market, because it supports the perception that the market is established and provides confidence that investors have a target against which to measure performance.

Unlike senior debt, information about high-yield debt is not nearly as readily available. High-volume lenders such as banks, pension funds and insurance companies not only publicly disclose some information about senior loans, but they are generally willing to share with index creators that aggregate the data. Mezzanine lenders, on the other hand, tend to be private equity firms that want to keep information closely held, in part because many advertise their ability to exploit mispricing in the market.

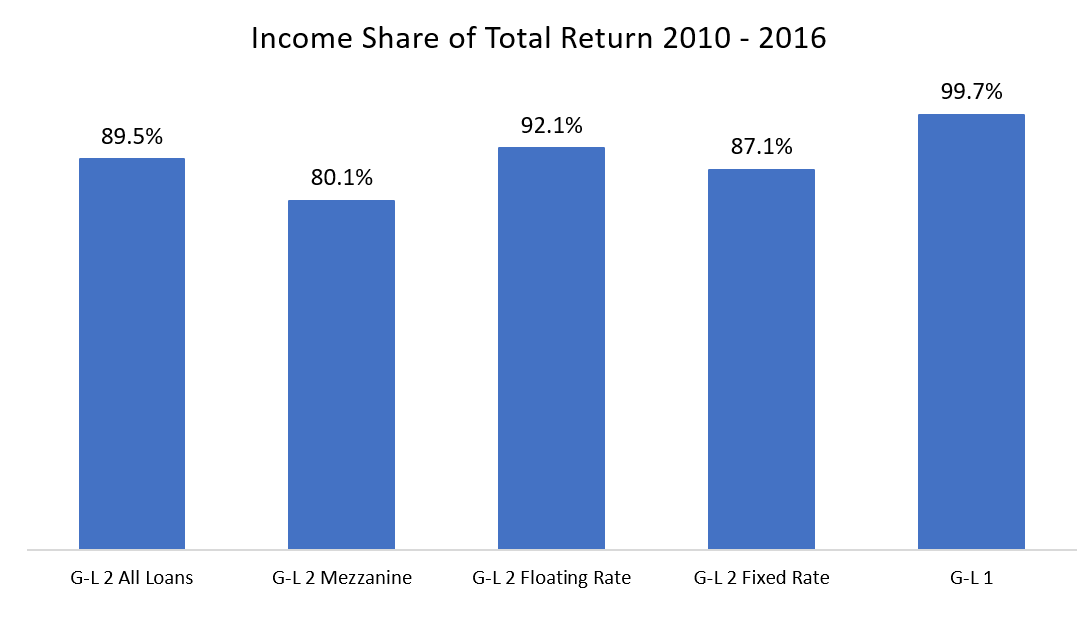

The high-yield index tracks the performance of $6.9 billion in high‐yield loans dating back to January 2010, representing a mix of property types. High-yield debt racked up a 7.6 percent average annual return from 2010 through December 2016, dramatically eclipsing the 5.3 percent return achieved by the firm’s senior‐loan index over that same timeframe. For 2016, investments tracked in the G‐L 2 produced a 9.4 percent return. Returns on mezzanine loans in 2016 were 10.4 percent.

Multiple categories of mortgages make up the high-yield index, with mezzanine loans (53 percent) and senior‐B notes (32 percent) representing the largest two components. Others include second mortgages and preferred equity, with 62 percent subject to adjustable or floating interest rates.

High-Yield Debt Hard to Measure

Mezzanine loan investments proliferated in the run-up to the last financial crisis. Many lenders originated loans of up to 95 percent of asset value and either held or securitized the senior portion (usually the top 50 to 70 percent of the capital stack), and sold the junior portions to high-yield investors. In large deals, the mezzanine classes were “tranched” and each class was sold to a different investor.

That turned into disaster when the financial crisis hit in 2008. Property values slipped and many mezzanine investors lost huge amounts of capital as their investments turned underwater. In deals with multiple junior classes, the multitude of mezzanine investors were forced to fight over control of properties.

The experience helped fuel demand for a performance index, but it also illustrates the difficulty in creating and maintaining an index. Each mezzanine loan represents a different portion of the capital stack, and is subordinate to a senior loan, which have different terms regarding how to handle reserves and default situations.

“All mezzanine loans are not created equal. Senior loans are more homogenous,” said one veteran debt investor who worried that an index could create “confusion.”

Said another: “Since mezzanine debt is typically heavily tranched, a ‘one size fits all’ index probably does not fit all.”

The high-yield index is available on a subscription basis, and subscribers can customize report components to align with their given investment profiles. The results will be published quarterly, starting with 2017 results.

“Industry experts worldwide have come to rely upon the G‐L Indices,” said Giliberto. “By providing total rate of return data that tracks income, price movements and credit effects, the G‐L Indices offer valuable insight into important market dynamics.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.