Are Utilities Ready for Smart Buildings?

Taking on the pivotal question about grid-interactive efficient buildings, a new study finds mixed results.

Image courtesy of San Diego Gas & Electric

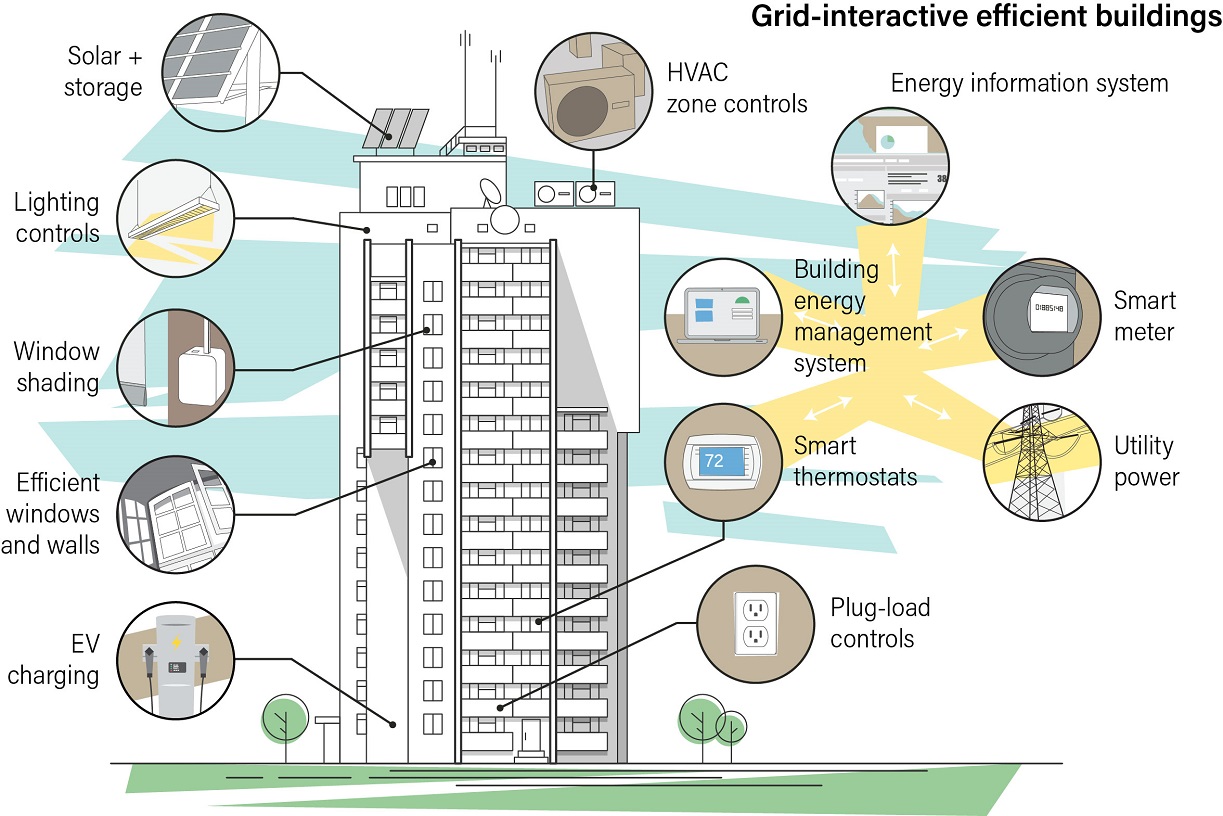

One of today’s highly promising innovations in energy operations is grid-interactive efficient buildings. Referred to as GEBs, these structures are connected to the grid and draw on distributed energy sources. Among other benefits, GEBs offer hold the potential to lower property operations costs.

But are utilities keeping up? A new study from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy tackles that question.

Deep Roots

The roots of today’s GEBs go back to the 1970s, said Dan York, an ACEEE senior fellow and co-author of the report along with Chris Perry, research manager for the organization’s buildings program and Hannah Bastian, an ACEEE researcher. A utility needing to shed load could send a remote signal to cycle off a building’s air conditioning equipment, he said. “In exchange for cycling it off, the customer would get a bill credit, but the interruption would be so small the customer wouldn’t notice,” York noted.

Today’s smart technologies take this concept considerably further. Solar energy, electric vehicles and battery storage combine to create a far more dynamic connection with utilities, at a time when power providers are seeking more flexible loads.

- Power from fully-charged car batteries can be fed to the grid. Grid-connected smart thermostats can cycle off at signals from the grid.

- Boilers operated during non-peak hours can heat water that stays hot during peak demand.

- Ice can cool buildings during the hottest times of day, when power is also most expensive.

This represents an evolution away from the conventional one-way system where utilities send power to customers to a new paradigm where the grid operator anticipates and manages loads. That operator can leverage breakthroughs in connectivity to send signals to buildings, and the buildings can respond by, among other actions, cycling off loads like high-demand lighting and air conditioning. Cycle off the A/C for five minutes, and it won’t be noticed, York said. But when the same step is repeated across thousands of units, it can lower peak demand system-wide, he added.

Even in the past 25 years, the grid has become much more complicated to operate. “It’s really about shifting time of uses to reduce costs,” York said. “Building owners are also finding some less quantifiable benefits from technologies that allow fine tuning for improved comfort in indoor working environments.”

Multiple barriers

Key elements of a grid-interactive efficient building, Diagram courtesy of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy

The chief barrier to making this all work is interoperability, said Chris Perry, research manager on ACEEE’s buildings program and a co-author of the report, along with Hannah Bastian, an ACEEE researcher. “Ability to communicate back and forth between buildings, the grid and aggregators is all pretty nascent,” he said. “There’s no real good language right now to talk to a utility or aggregator. This isn’t something we’ll see in a year or two. It’s years down the line.”

Two other barriers also loom large. One is cybersecurity, which York calls “the downside of all this interconnectivity.” The other centers on workforce issues. Building engineers need to understand how to make it all work, York said.

Meantime, building owners can prepare for the days when these kinks are ironed out. As they upgrade or undertake new construction projects, they should seek equipment capable of being connected. An example of current equipment letting owners/operators take advantage of demand-response programs is the smart thermostat, York said.

“It’s not always going to be about shedding load,” he added. “It might be about contributing power to the grid, where the customer becomes a supplier of energy from the photovoltaic system on the roof, or from battery storage.”

Leaders and laggards

Duke Energy’s electrical substation, Harrisburg, North Carolina. Image courtesy of Duke Energy

According to Perry, the universe of U.S. utilities includes some that are ahead of the curve on GEBs. Others, he said, “are intrigued by buildings being a resource for them, but are in the early stages of investigating what programs would look like.”

Among the leaders in adoption cited by the study are ConEd’s Brooklyn-Queens Demand Management project; New York State Energy Research and Development Authority’s Real Time Energy Management program; NV Energy’s Business Solutions Center program; and AEP Ohio’s It’s Your Power program.

Those utilities that have gained experience with energy efficiency programs; established relationships with customers; ensure the right equipment is used; and that it will continue to operate correctly are in the forefront of leveraging the new capabilities, York said. “The utility business is different than it was even 10 years ago,” he noted, adding, it now involves a much more collaborative partnership where utilities seek to become trusted partners and reliable sources of information, and look out for customer interests.

Progressive building owners and utilities recognize the emerging opportunity GEBs offer and will work together to realize benefits during this time of dynamic change, York observes.

The grid-connected part is a big step but by no means a prerequisite, he maintains: “But it’s still very possible for building owners to have smart controls and highly efficient, high-performance buildings even in the presence of a utility not exploring these opportunities.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.