CPE Executive Council: How Institutional Investors are Shifting Their Focus

What's driving investment strategies, and how to adapt to an uncertain economic environment.

With an uncertain economic climate, institutional investors are changing their focus in commercial real estate. The CPE Executive Council shares the biggest areas of change.

New Property Types

Institutional investors continue to evaluate their commercial real estate strategy with new property types emerging and traditional product types coming back into favor. Single-tenant net lease is gaining steam again as is IOS and single family rental. Industrial and retail remain stable. Finally, assets poised for conversion are definitely getting a strong look today. —Dave Ebeling, Owner, Ebeling Communications

Complex Landscape

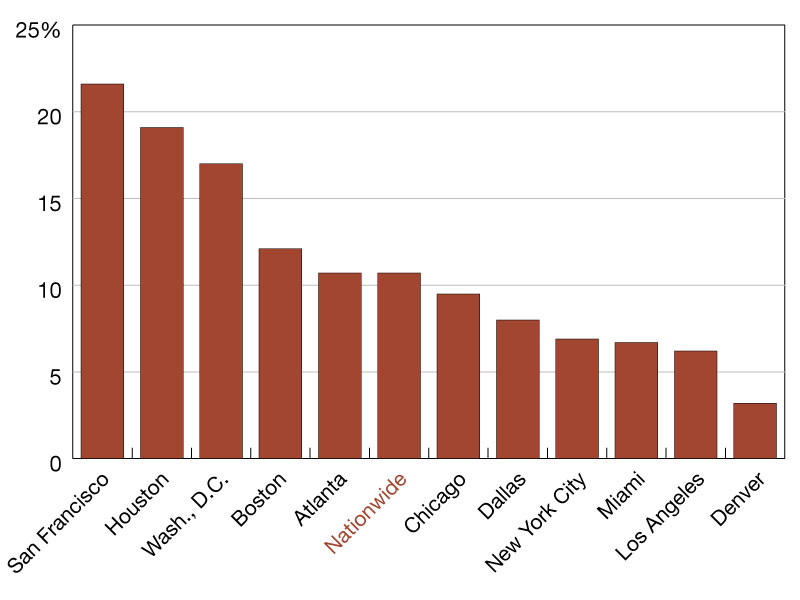

The commercial real estate market presents a complex landscape for institutional investors as it recovers unevenly from recent challenges. Multiple forces are reshaping investment strategies: declining interest rates provide relief while maturing loans create pressure points, and geopolitical tensions add uncertainty to an already volatile environment. Meanwhile, transformative trends like AI integration and growing sustainability requirements are fundamentally altering property demand and valuations.

Three key themes are driving investment decisions: the search for inflation protection in an uncertain economic climate, the need to capitalize on digital transformation reshaping how properties are used and valued, and a pronounced flight to quality as investors prioritize stability and growth potential over yield alone. —Randy Blankstein, President, The Boulder Group

Addressing Housing Issues

Parties have blamed professional housing providers for the ongoing affordability crisis. In Congress, Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.) and Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) have introduced legislation to impose tax penalties for institutional investors buying single-family homes or even to force them to sell any single-family homes they have purchased. Several states have followed suit.

This rush to ban certain entities from owning homes flows from a misunderstanding of their effect on the housing market and their small presence in the single-family housing market. Evidence shows institutional investors in housing rarely displace individuals from the housing market or increase prices, but local government restrictions certainly do reduce housing supply and drive up prices.

Professional housing providers first significantly appeared in the aftermath of the 2008 housing and financial crisis. Before 2011, no investors owned more than 1,000 units. After the housing crash, investors purchased foreclosed homes, anticipating a rebound. This helped to balance the mass exit of individual homebuyers and prop up housing prices that were in freefall, which meant significantly fewer abandoned homes and dilapidated neighborhoods.

Today, institutional investors only own about 2 percent of single-family housing in the United States, which is far from a crisis. They did not displace individuals or families—census data show that the homeownership rate in the US increased by over 2 percent since 2015, even as investor ownership grew.

Professionally managed housing provided a much-needed increase in the supply of single-family rental housing. The Government Accountability Office found that, over time, institutional investors are increasingly paying for the construction of new rental houses rather than buying existing homes. The Urban Institute has pointed out that institutional investors tend to purchase homes in need of repair and “can repair these properties more quickly and efficiently than an owner-occupant generally can.” Fixer-uppers cost less, and with economies of scale, institutional investors can repair a large number of homes at lower cost.

Blaming institutional investors distracts focus from addressing real housing problems. The market is not acting as the critics of institutional investors say. If investors are driving up prices, the natural market response would be to increase supply so that homebuilders could sell to both investors and families. If supply keeps up with demand, prices won’t fluctuate much. But while prices did increase, housing supply hasn’t kept up. Persistent regulatory barriers, including zoning restrictions, minimum lot sizes, limits on multifamily housing, and long and costly permitting processes have made it difficult, if not impossible, to meet the rise in demand in a cost-effective way. According to a recent paper in the National Bureau of Economic Research, barriers to building have led to fewer homes being built. In fact, the paper finds that “If the U.S. housing stock had expanded at the same rate from 2000-2020 as it did from 1980-2000, there would be 15 million more housing units.”

It is not the infusion of capital from investors that disrupts housing markets; it is local government policies that do not let supply keep up with demand, creating a shortage that attracts investors. The increased involvement of investors in the housing market should be a wake-up call to policymakers. Housing supply should be able to fulfill the needs of both the single-family rental and the for-ownership sectors of the broader housing market. —Doug Ressler, Manager, Business Intelligence, Yardi

Interested in joining the CPE Executive Council and being featured in future articles? Email Jessica Fiur.

You must be logged in to post a comment.